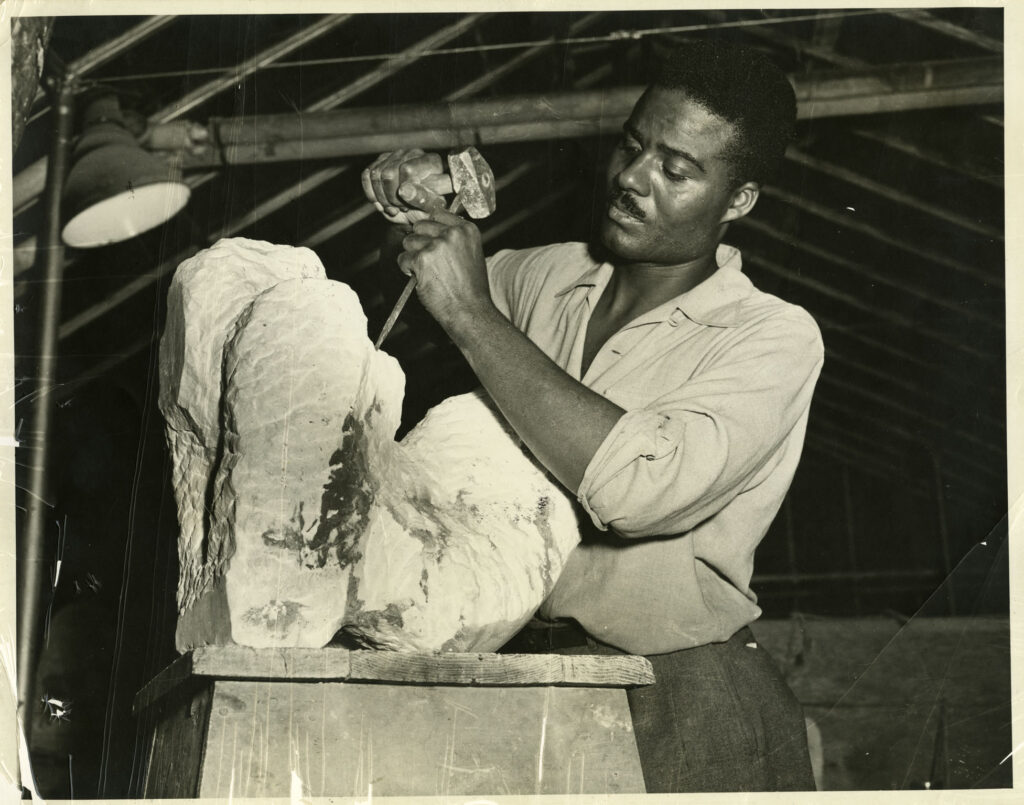

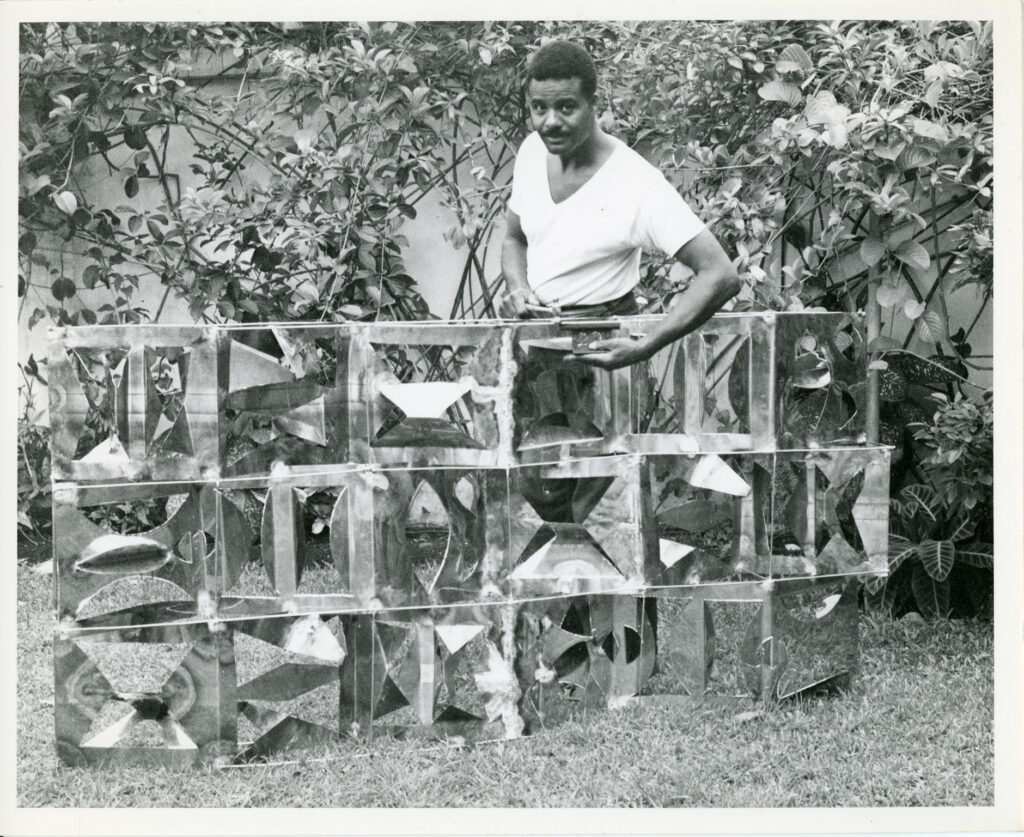

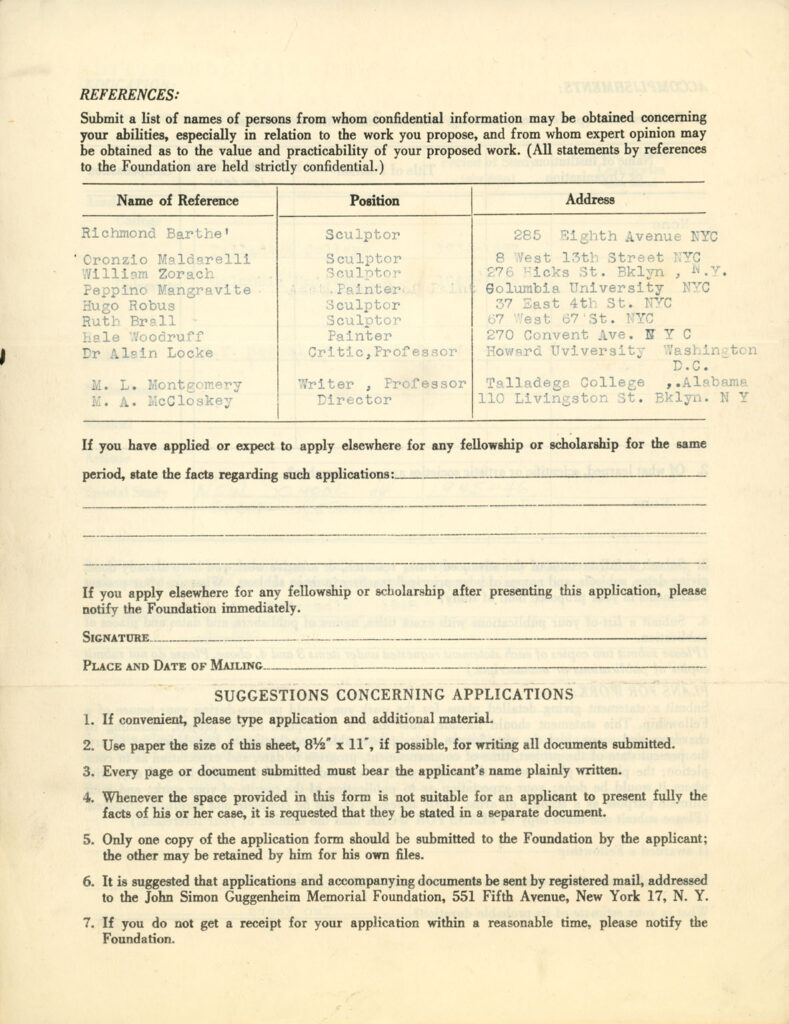

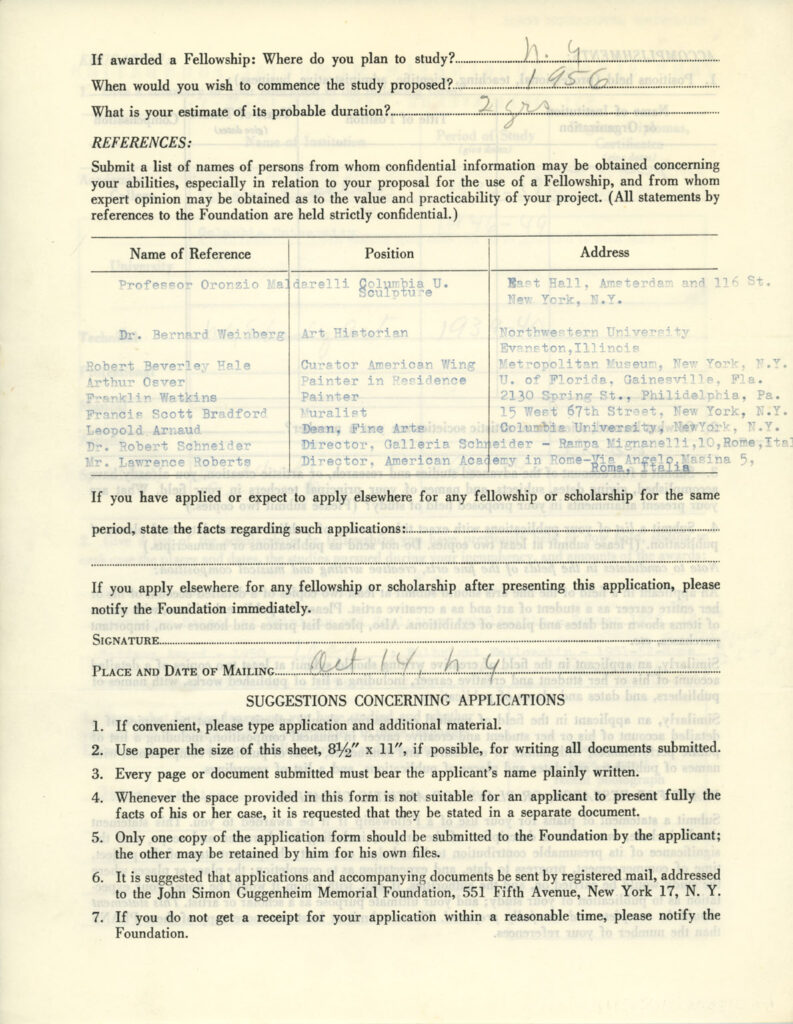

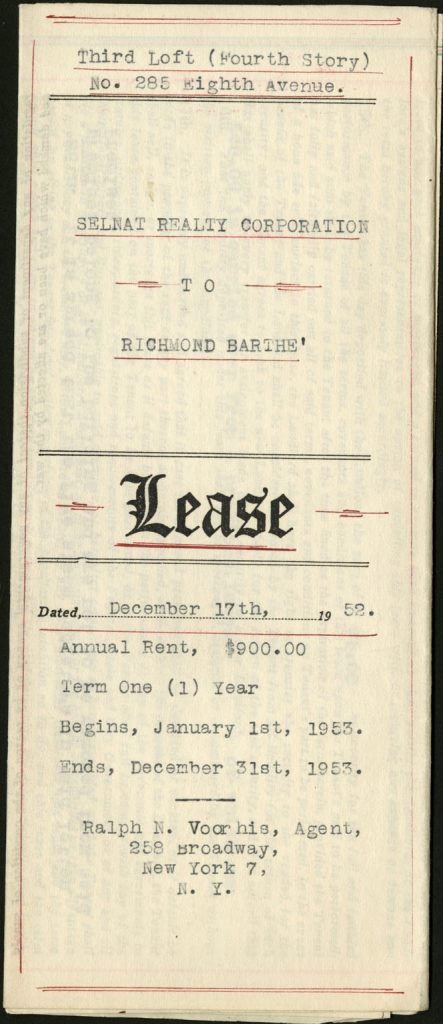

Contributed by Jahna Auerbach, Assistant Archivist for the John Rhoden papers

The John Rhoden papers have not only given us historical insight into John as an artist but great visual insight into American and international culture from the late 1930s through the 1990s as well. I wanted to take the time to highlight one of my favorite aspects of the collection, the clothing and fashion. We’ll start with the best representation of fashion over time in the collection: the outfits of Richenda Rhoden.

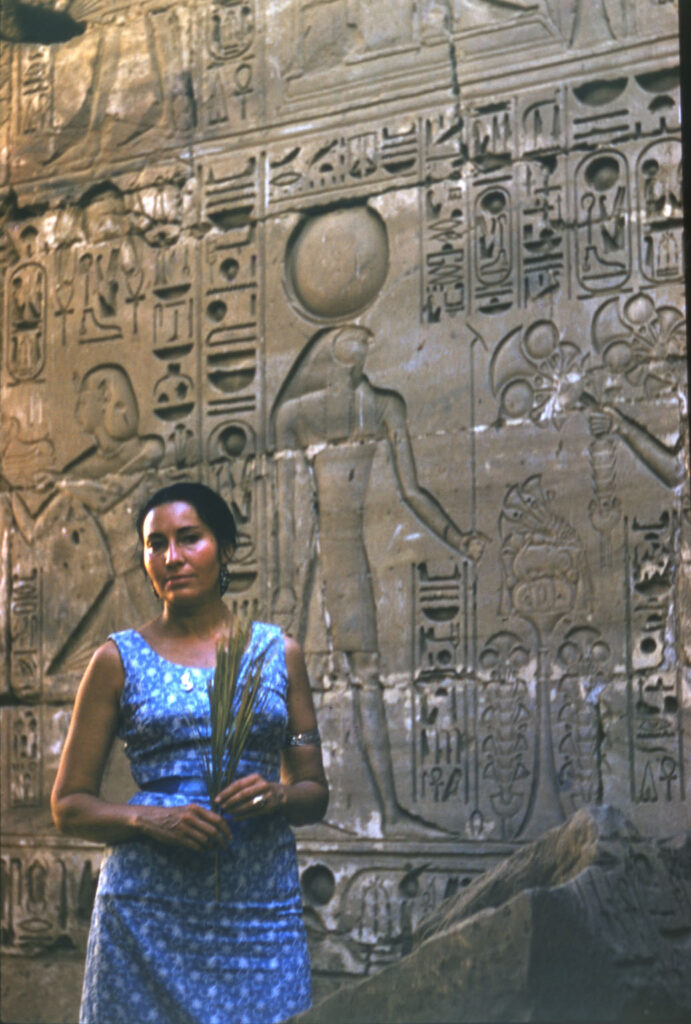

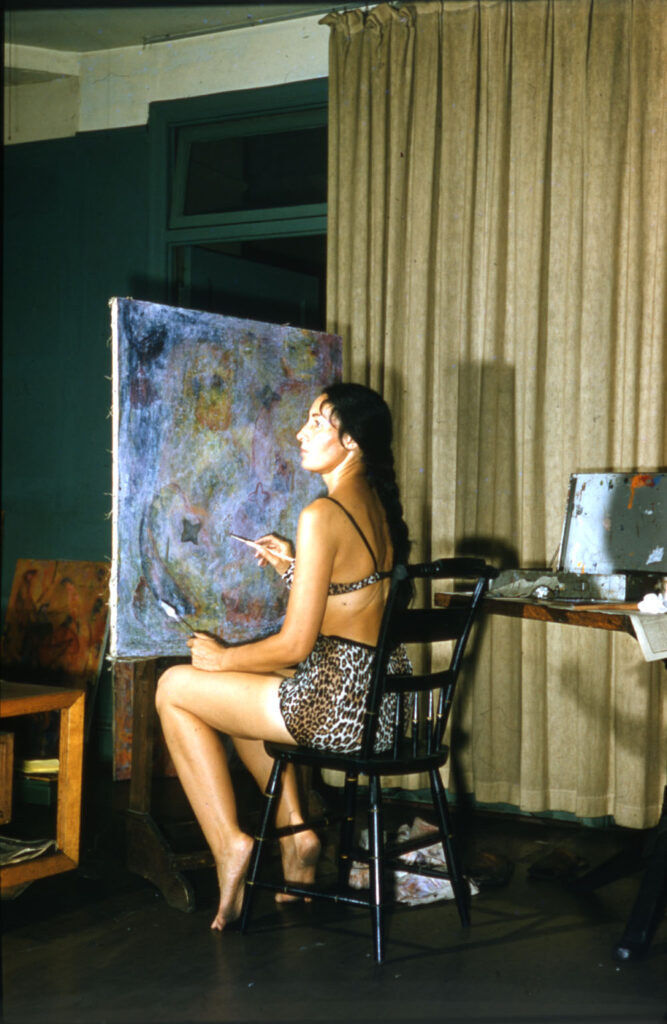

I first became interested in Richenda through the many photographs and travel slides in the collection. These images aren’t just fun to view; they also give context for how Richenda expressed herself as a Native American woman during the 20th century. By viewing event photos, candid shots, and hundreds of travel slides, we can see more than ‘Richenda Rhoden the model,’ or ‘Richenda Rhoden, John’s wife.’ Instead, we see a strong and insightful woman, an artist in her own right and a person unwilling to hide her own beauty and style.

Below, we explore her travels, see her at home, and a personal favorite, in her bikinis and endless leopard print. Instead of looking at the fashion of bygone celebrities or Vogue, archival depiction of fashion reveals how everyday people dressed. It captures the personality and variety in a way that the established fashion resources can’t. Not everyone updates their closet every year or throws out an outfit once it’s out of style, so it’s only natural that the fashion authorities might not have their finger to the pulse of what real people wore.

Egypt, circa 1955-1959

Italy, 1954

circa 1951-1959

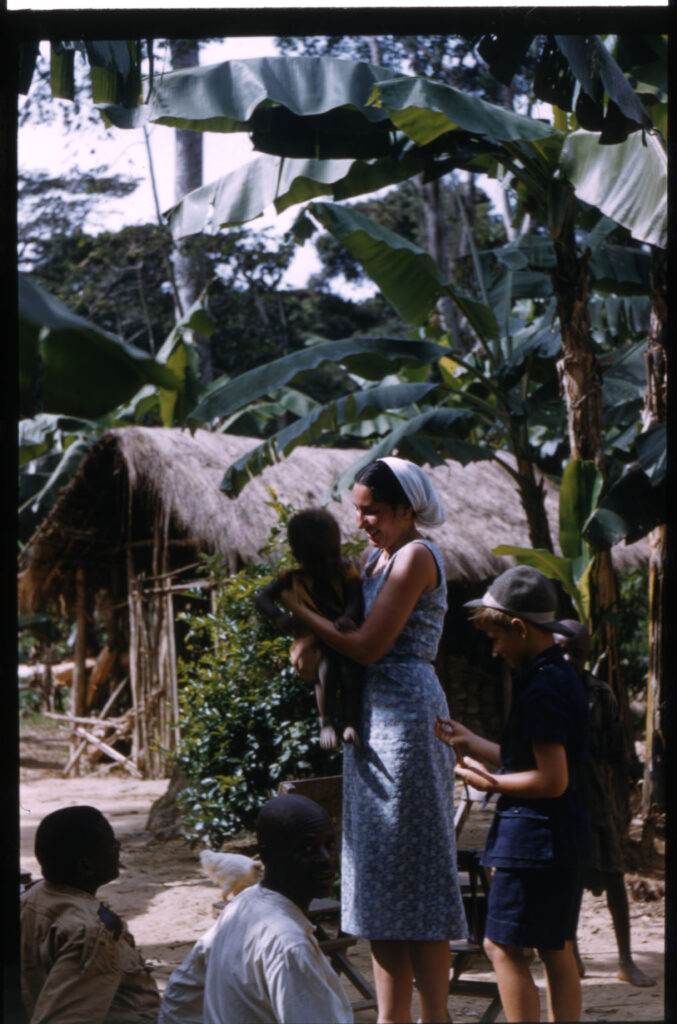

Africa, circa 1955-1956

When Richenda traveled with John in the ‘50s and ‘60s she wore many classic silhouettes common to the era. Some of her favorite outfits were blouses with a full skirt, often paired with a headscarf and belt. Many of her travel outfits also include fitted blazers and suit sets, as well as full-skirted dresses.

Egypt, 1958

Turkey, 1958-9

possibly Iran, 1955-9

Italy, circa 1951-1954

Egypt, circa 1951-1957

The 1960s fashion was dominated by innovation and bohemian style inspired by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and youth culture. For the most part, Richenda did not follow these trends. However, she did have a few staple outfits that fit the decade in her bathing suits and leopard print outfits.

Indonesia, 1963

Brooklyn, 1960s

Leopard print was made famous by celebrities like Marilyn Monroe. Richenda’s leopard print catsuit reflected real 1960’s fashion, exuding style while still being comfortable.

Throughout her life, Richenda kept many staples from the 1950s in her wardrobe. For example, Richenda’s swimsuit in Bali is more reminiscent of a 1950’s bikini, with high waisted bikini shorts and a matching bra top.

Indonesia, 1963

Indonesia, 1963

Some of Richenda’s best outfits were worn in her own home. She was regularly photographed in the garden, posing with her art, or with the family Christmas tree. Her at-home clothing choices do not reflect a period in fashion. Instead, they show how Richenda expressed herself – primarily in boldly patterned dresses.

Brooklyn, 1960s

Brooklyn, 1994

Brooklyn, 1960s-1970s

After taking the time to study Richenda’s fashion, I’m left with more questions than answers. I wish more than ever that I could sit down and have a conversation with her. I would gain insight into how she dressed as a Native American, how her travels in Europe and Asia affected her self expression, and how she wanted to present herself as a woman, artist, and partner to John Rhoden.

This project, Rediscovering John W. Rhoden: Processing, Cataloging, Rehousing, and Digitizing the John W. Rhoden papers, is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation. Additional information about the National Endowment for the Humanities and its grant programs is available at: www.neh.gov.