PAFA is excited to welcome Sharon Yoon as our new Museum Collections Assistant. Sharon recently completed her bachelor’s degree at Drexel University studying Art History. She will help support many activities that help promote the care and use of the collection as help conduct research.

Digital Treasure Trove: Parallel projects-John Rhoden sculptures

Contributed by Adrian Cubillas, Photographer and Digital Collection Coordinator & Zoe Smith, IMLS Project Museum Collections Assistant

PAFA’s Digital Treasure Trove project and the exhibition Determined to be: The Sculpture of John Rhoden both embody the institution’s mission by expanding the stories of American art. The grant project preserves and makes artworks more accessible to the public, while the exhibition showcases the work of an artist whose contributions challenge conventions and broaden the understanding of American art. Together, these projects reinforce our commitment to inspiring and educating through its world-class museum and school. For the Rhoden exhibition, Dr. Brittany Webb, Evelyn and Will Kaplan Curator of Twentieth Century Art.

John W. Rhoden (1916-2001). Three Headed Lion, 1954. Bronze, The John Walter Rhoden and Richanda Phillips Rhoden Collection, 2019.27.3

Zoe and I had the pleasure of attending the opening of Determined to be: The Sculpture of John Rhoden. We were lucky enough to walk through the exhibit as it was being installed with the curator Dr. Brittany Webb. Getting to see the behind-the-scenes as well as the final exhibit was a great experience that opened my eyes to how much goes into creating such a big show. We also had the amazing opportunity to make some gifs of the sculptures to promote the show! (see below). We loved being able to contribute to such a wonderful project.

Digital Treasure Trove: Project Update

Contributed by Hoang Tran, Director of Archives & Collections and Zoe Smith, IMLS Project Museum Collections Assistant

It’s been a busy summer at PAFA. At the end of June, we had to say good-bye to our IMLS Collections Assistant L. L had an amazing job opportunity to work for a local artist as a studio assistant. We wish L all the best and thank them for all their hard work and dedication! L’s work helped us hit major milestones on the project–completing 99% of works on paper photography, completing all subject terms in the catalog records, and pushing us over 60% completion of the project!

We were fortunate to rehire the position quickly. Our new IMLS Collections Assistant is Zoe Smith who started August 21, 2023. Please read Zoe’s introduction blog below:

My name is Zoe Smith, I am a recent graduate of Drexel University where I completed a bachelor of science in photography. I have a love of nature and art that merges into the work that I make. I am passionate for printing my photographs, and experimenting with alternative printing methods. I am extremely excited to use my photographic experience to contribute to the art world by updating PAFA’s amazing collection of art. This task feels exceptionally important to me, and I hope people are able to learn and grow from this fantastic resource.

My work at PAFA consists of assisting in photographing and digitizing the extensive collection of paintings, sculptures, and other works of art. Being able to look into the history of each one of these objects is an immense privilege that I am very much looking forward to.

My first week here I dove right in and began photographing various medallions. The intricate carvings on each of these surfaces have been a fun challenge to photograph. Using a lightbox to evenly light the subject, we have been using multiple exposures to get different parts of the medallion perfectly in focus. This is necessary because of the various depths of the carving on these objects.

After photographing I have been bringing the 2 to 6 exposures into a focus stacking software and combining them into one photo. This technique can be challenging and it has been great training my eye to see the slight differences in focus. I am looking forward to using the same technique on small busts and sculptures. Each artwork poses an exciting new challenge in photographing that has been very rewarding. I love to imagine the thousands of people before me that have had a connection to this art, which deepens my own personal connection to it.

About the Institute of Museum and Library Services

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s libraries and museums. We advance, support, and empower America’s museums, libraries, and related organizations through grantmaking, research, and policy development. Our vision is a nation where museums and libraries work together to transform the lives of individuals and communities. To learn more, visit https://www.imls.gov/and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Digital Treasure Trove: Unwanted Reflections

Contributed by PAFA Museum Collections

One of the many challenges we face when photographing works from the collection is avoiding different kinds of unwanted reflections. Even small adjustments to our lights can result in everything from an overpowering glare to a flattening of any surface texture in the final image. Even trickier is dealing with works that are behind glass/plexiglass, which often reflect the environment back like a mirror.

Addressing this requires making sure that anything within the frame of the shot is cloaked in dark fabric, which won’t reflect enough light to interfere with the image. In addition to cloaking the equipment, we also must ensure that we personally are kept behind the fabric when operating the camera. At times it can look a little odd, but it goes a long way in improving the quality of the museum’s documentation of work.

About the Institute of Museum and Library Services

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s libraries and museums. We advance, support, and empower America’s museums, libraries, and related organizations through grantmaking, research, and policy development. Our vision is a nation where museums and libraries work together to transform the lives of individuals and communities. To learn more, visit https://www.imls.gov/and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Student Stories: Internship Experience

Contributed by Catherine Wan, intern

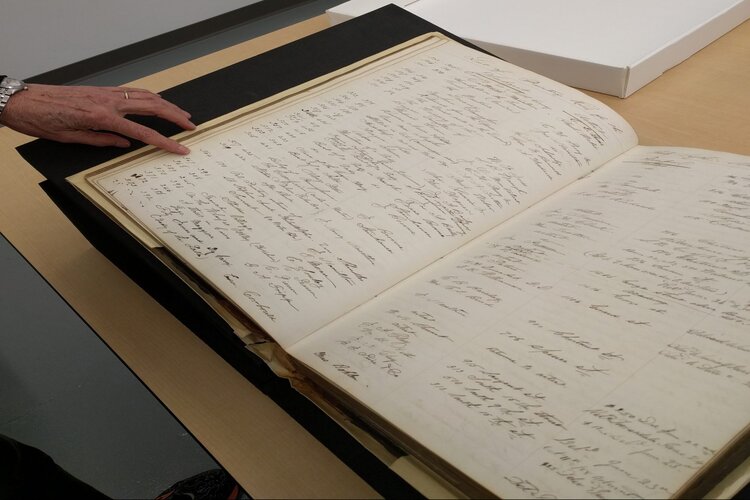

I write many essays and never give much thought to the creation of the primary sources I use. The databases, articles, and journals are all simply online. However, this internship has allowed me to participate directly in the creation of a digital collection comprised of primary source documents and photographs.

The digital collection will showcase archived documents from Asian students who attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1917-1949. The work will help support PAFA’s initiative to highlight historically marginalized groups in the US. As a Chinese American, a history major, and someone interested in art, the chance to put a spotlight on these students is very important to me.

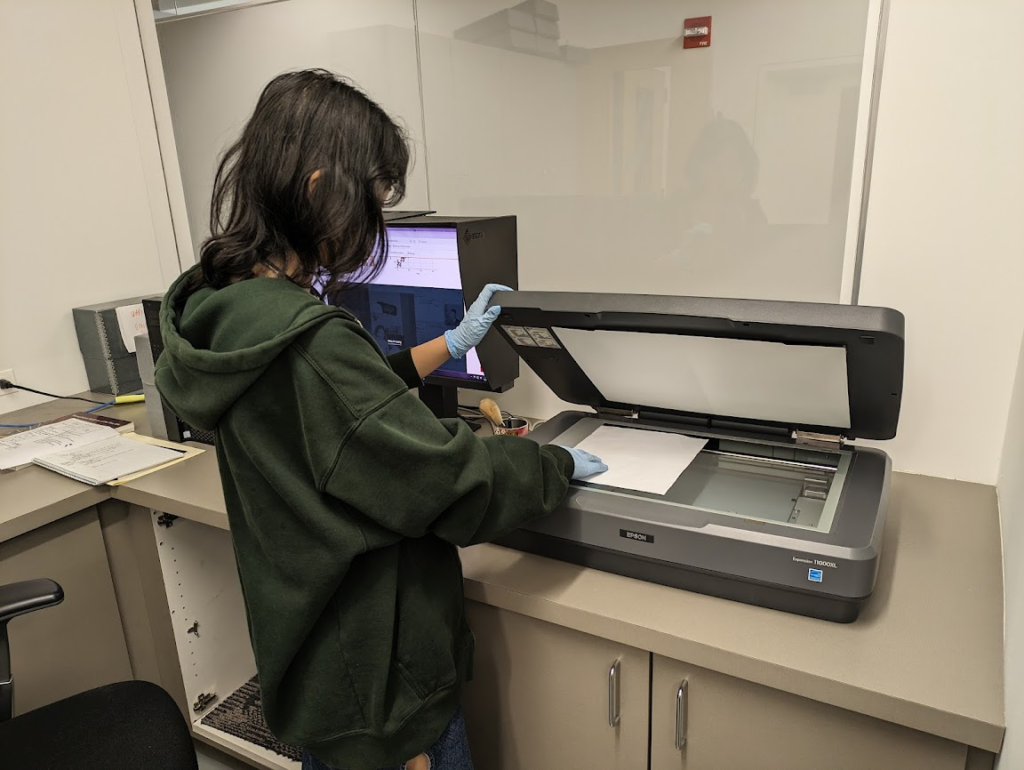

My work of scanning, formatting, and cataloging has allowed me to hold the delicate, aged papers these students once poured their hopes into. Each document describes their unique view of art and beauty, and their willingness to contribute to the field. The process of digitization ensures that this section of their life spent at PAFA will not fade nor remain hidden from the public. Instead, these newly digitized records will be preserved digitally and available freely online.

Like many general users, I didn’t realize all the necessary steps that were required to create digital collections. During my work in school, I never thought about how the digital records/collections came to be. Now, I was part of the creation process! I have the satisfaction of contributing a bit to the sea of online resources for users.

Intern Spotlight – Catherine Wan

Contributed by: Hoang Tran, Director of Archives & Collections

The archives is excited to introduce this years summer intern, Catherine Wan. Catherine is currently an undergraduate student pursuing a history degree at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. For the summer internship project, she will help identify, digitize, catalog and research student academic files. Since Catherine has a strong interest in Asian history, the project will focus on students of Asian descent.

In typical PAFA fashion, Catherine jumped into the project and began working diligently. Digitizing and cataloging were the first part of the project.

The next phase of the project will be researching and analyzing the data to form new knowledge. This internship project contributes to the Archives’ hidden histories initiative by identifying and researching untold stories from underused areas of PAFA’s collections.

Digital Treasure Trove: The Watercolors of William Trost Richards

Digital Treasure Trove: The Watercolors of William Trost Richards

Contributed by PAFA Museum Collections

For the last several photography sessions, the collections team has been working to photograph a unique set of small watercolor paintings by the artist William Trost Richards (1833-1905). With some slight variations, the dozens of paintings are each only a little larger than 3×5” and depict a range of beautiful wide-angle landscape scenes. The images are executed in striking detail for their scale and medium. Together, the works demonstrate a superior command of light and texture. It has been a pleasure to spend time photographing these works, and once the project is finished, they can each be viewed and enjoyed in significantly greater resolution.

William Trost Richards – Boats at Pier for Joseph Wharton’s Workmen, Conanicut Island (1883), Watercolor on paper, 3 3/16 x 5 1/8 in. (8.09625 x 13.0175 cm.). Gift of Dorrance H. Hamilton in memory of Samuel M. V. Hamilton, 2008.5.87

View more works by Richards on PAFA’s online database: https://www.pafa.org/museum/collection-artist/william-trost-richards

About the Institute of Museum and Library Services

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s libraries and museums. We advance, support, and empower America’s museums, libraries, and related organizations through grantmaking, research, and policy development. Our vision is a nation where museums and libraries work together to transform the lives of individuals and communities. To learn more, visit https://www.imls.gov/and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Setting up for the 122nd Annual Student Exhibition

Opening this month is PAFA’s Annual Student Exhibition (ASE), now celebrating its 122nd year. Our archives have a long practice and record of documenting the ASE, and its connection to student life here at the school and museum, like in the image here from 1910.

Below are some images of the installation process from this year’s exhibition, which span all three floors of the Samuel M.V. Hamilton Building.

Learn more about this year’s Annual Student Exhibition and its corresponding events here: https://www.pafa.org/school/annual-student-exhibition

Learn more about the history of the Annual Student Exhibition here: https://pafaarchives.org/page/ase

About the Institute of Museum and Library Services

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s libraries and museums. We advance, support, and empower America’s museums, libraries, and related organizations through grantmaking, research, and policy development. Our vision is a nation where museums and libraries work together to transform the lives of individuals and communities. To learn more, visit https://www.imls.gov/and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

122nd Annual Student Exhibition

It’s that time of year again! Students, faculty, and staff from the school and museum are actively working to complete the installation of the Annual Student Exhibition (ASE). ASE is considered a capstone event for BFA and MFA students that coincides with graduation.

ASE “Walls” vary from student to student, each pursuing an individual interest. The emphasis of the exhibition is on creating a cohesive body of related works through sustained studio practice and critical inquiry.

While the ASE is spearheaded by the school, the Museum also plays an active role in guiding and providing assistance to students. PAFA’s art preparators help students prepare their works to be hung, help with installation, and provide feedback on aesthetics.

Contract art preparator Travis Grant

PAFA Assistant Art Preparator Jacob Stevens

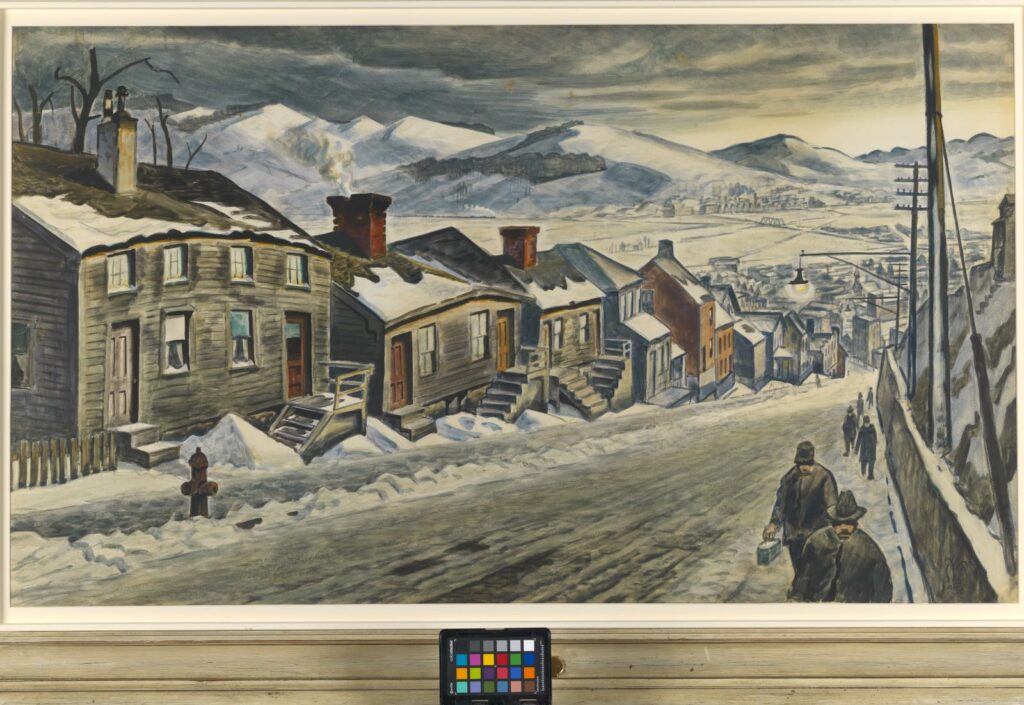

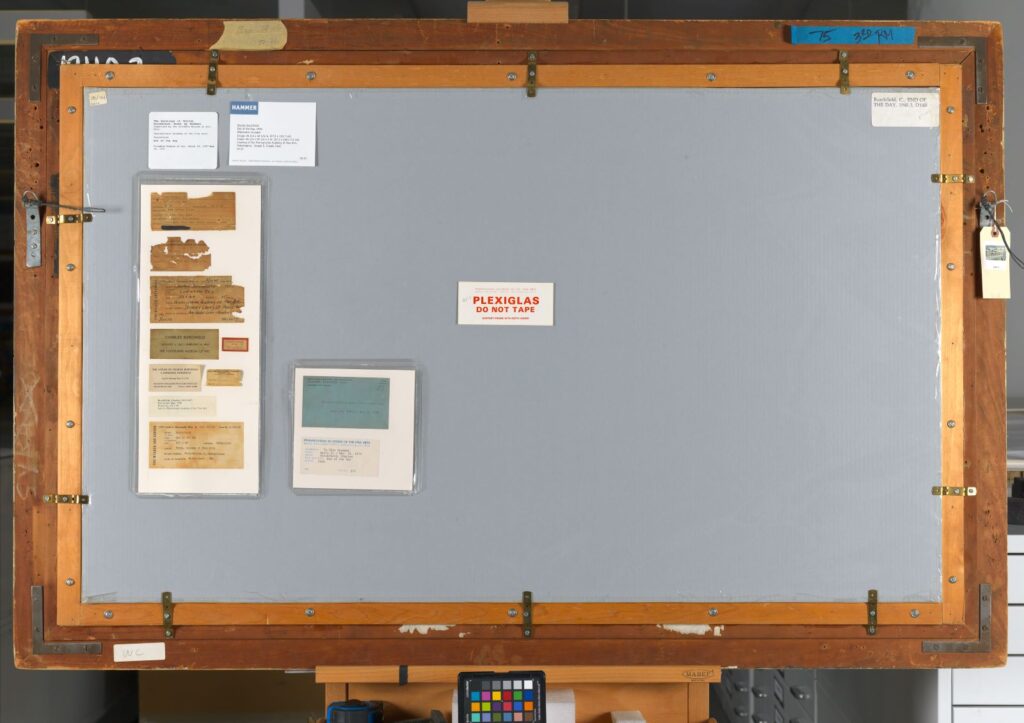

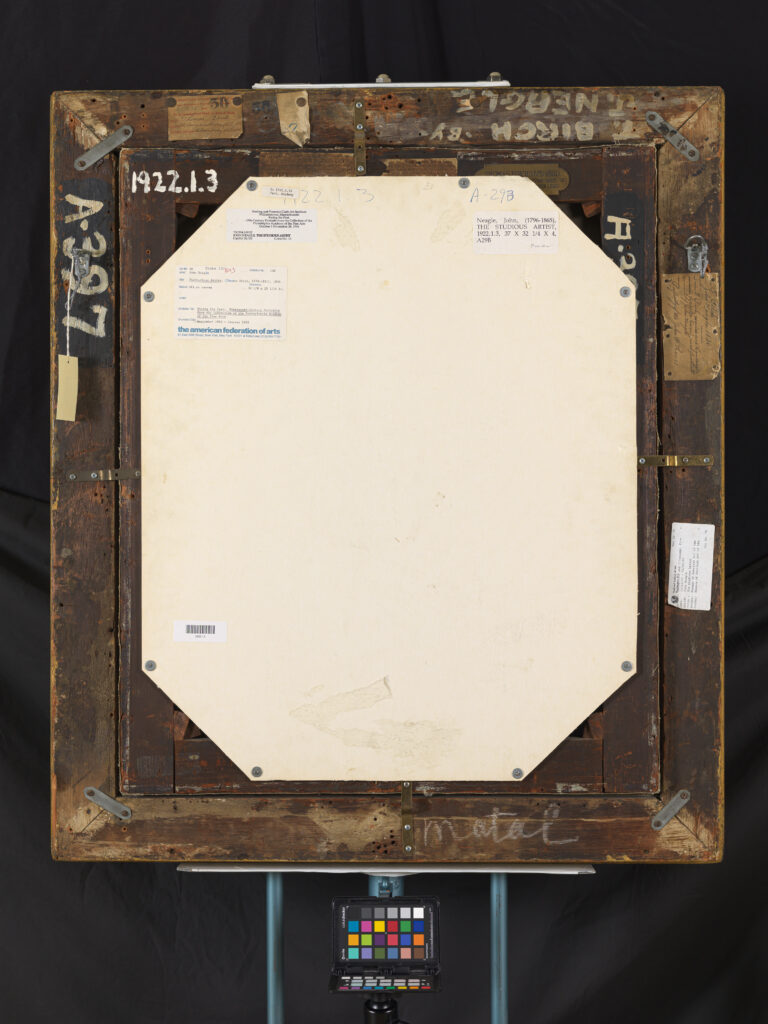

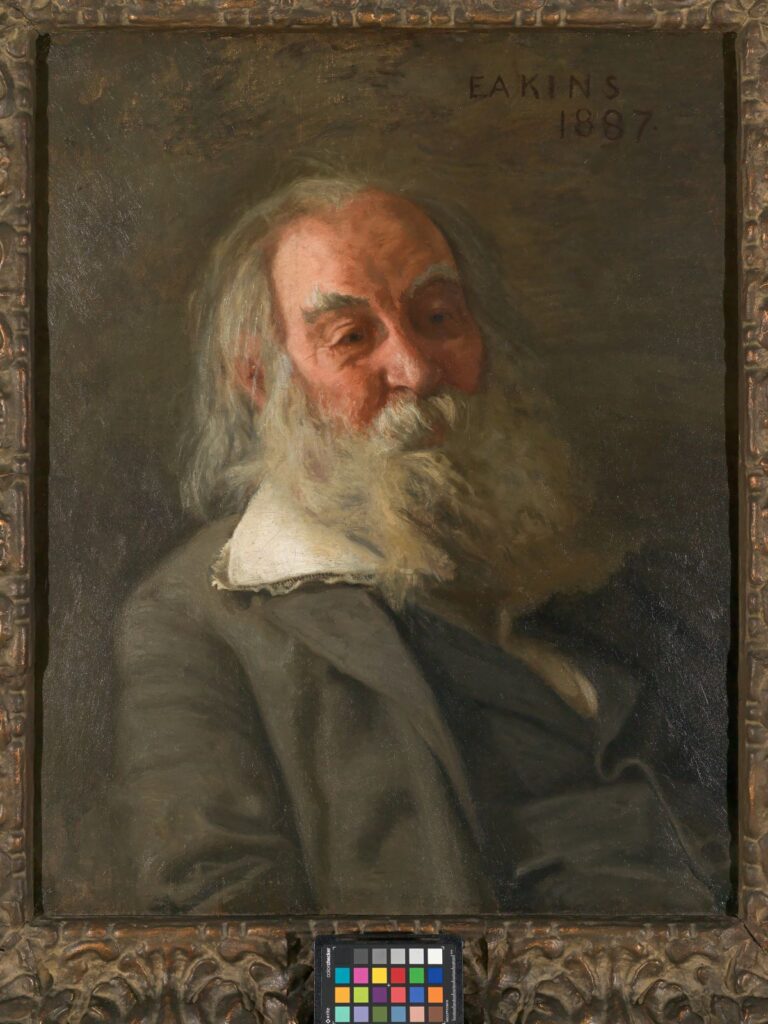

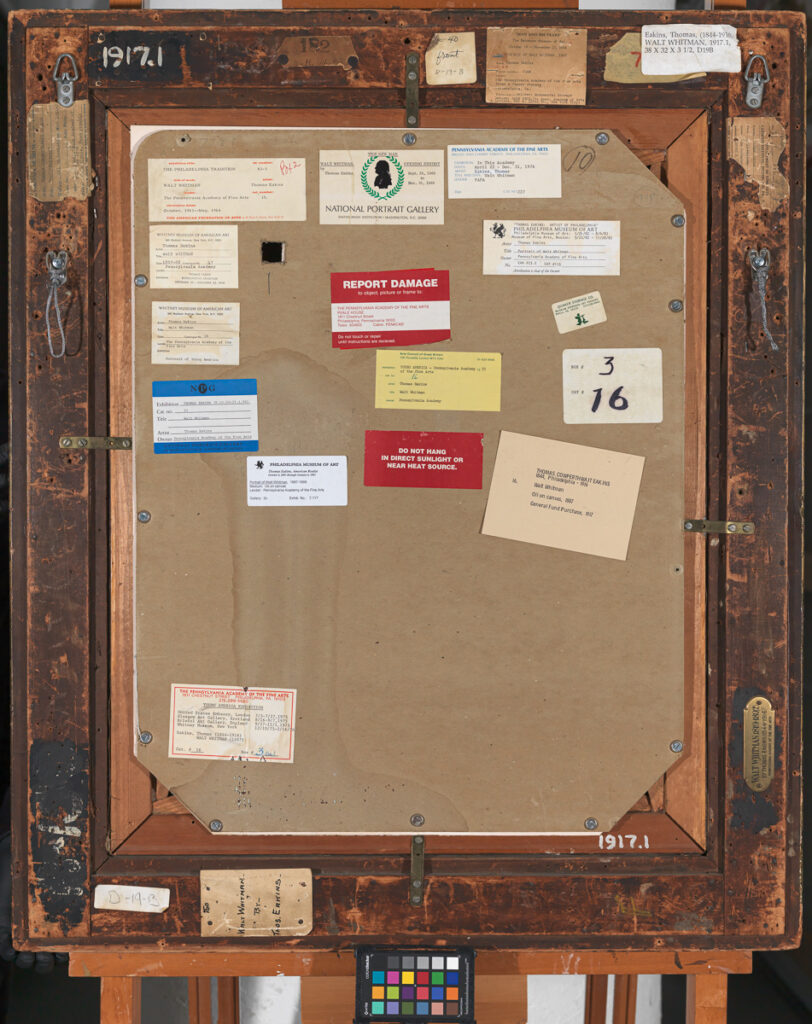

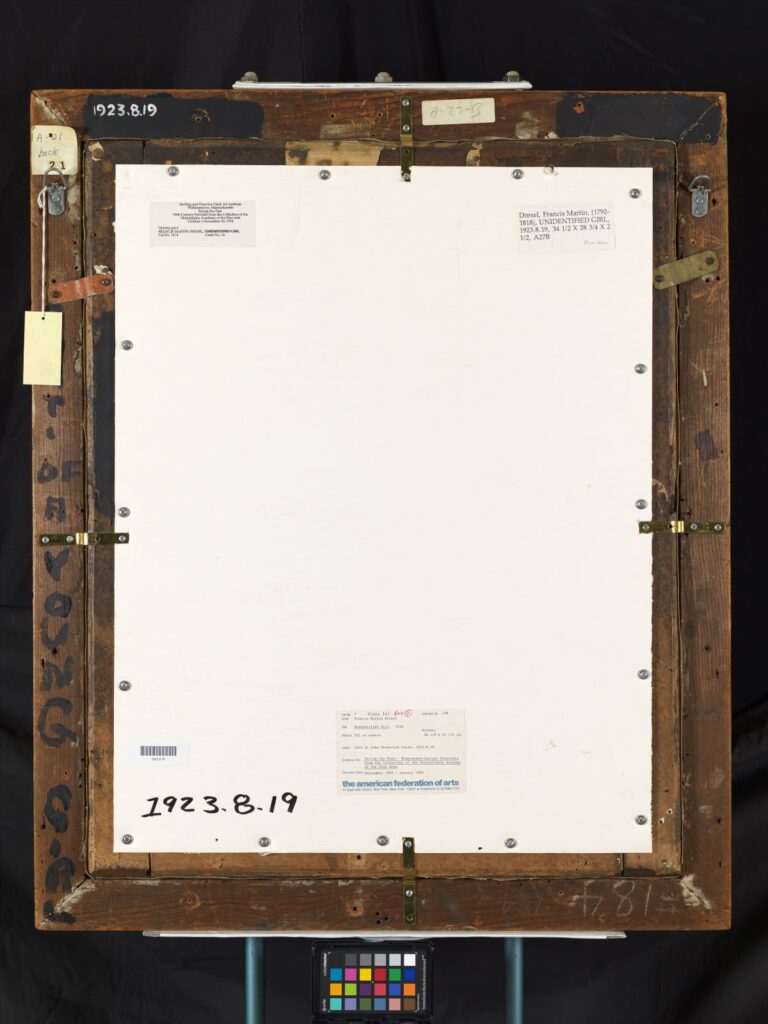

Digital Treasure Trove: Recto//Verso

Contributed by PAFA Museum Collections

As the collections team has been photographing some of PAFA’s framed paintings over the last several weeks, we have been able to enjoy documenting the rarely seen reverse side of these works.

In the museum world, we define recto as the front or main image and the verso as the back or reverse secondary image. So why may we want to photograph the verso?

Many paintings in our collection have a long exhibition and ownership history, and this provenance can be followed through various notes, labels, stickers, and other markings on the backs of frames. Pictured below are a few examples of works in the middle of being photographed showing the front side view (recto), followed by the corresponding reverse side of the painting (verso).

Charles Burchfield, End of the Day, 1938. Watercolor over pencil and charcoal on white paper, 28 x 48 in. Joseph E. Temple Fund, 1940.3

John Neagle, The Studious Artist, 1836. Oil on canvas. 30 1/8 x 25 1/16 in. Gift of John Frederick Lewis, 1922.1.3

Thomas Eakins, Walt Whitman, 1887. Oil on canvas, framed-shadow box: 38 1/8 x 32 1/4 x 4 in. General Fund, 1917.1

Francis Martin Drexel, Unidentified Girl, 1818. Oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 24 1/4 in. Gift of John Frederick Lewis, 1923.8.19

About the Institute of Museum and Library Services

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary source of federal support for the nation’s libraries and museums. We advance, support, and empower America’s museums, libraries, and related organizations through grantmaking, research, and policy development. Our vision is a nation where museums and libraries work together to transform the lives of individuals and communities. To learn more, visit https://www.imls.gov/and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.