Contributed by Sharon Yoon, Museum Collections Assistant

We’re excited to announce that the digitization of the Morris Gallery photographs is complete. You can browse the images on PAFA’s Digital Archives: https://pafaarchives.org/s/digital/item-set/159894 or view our dedicated Morris Gallery page here: https://pafaarchives.org/s/digital/page/morrisgallery

In 1978, PAFA established the Morris Gallery on the ground level of the Furness-Hewitt building with the specific intent of exhibiting contemporary work by living artists with Philadelphia ties. The Gallery has housed numerous exhibitions by influential artists such as Robert Ryman, Vik Muniz, Nan Goldin, Laylah Ali, Virgil Marti, Alyson Shotz, and Emil Lukas, among many others.

In addition, more conventional exhibitions focusing on art associated with the Academy or its traditions helped spread knowledge of the institution’s heritage and collections. As the program continually developed through the decades, it served as a showcase for a diverse array of artists from the Philadelphia region and beyond.

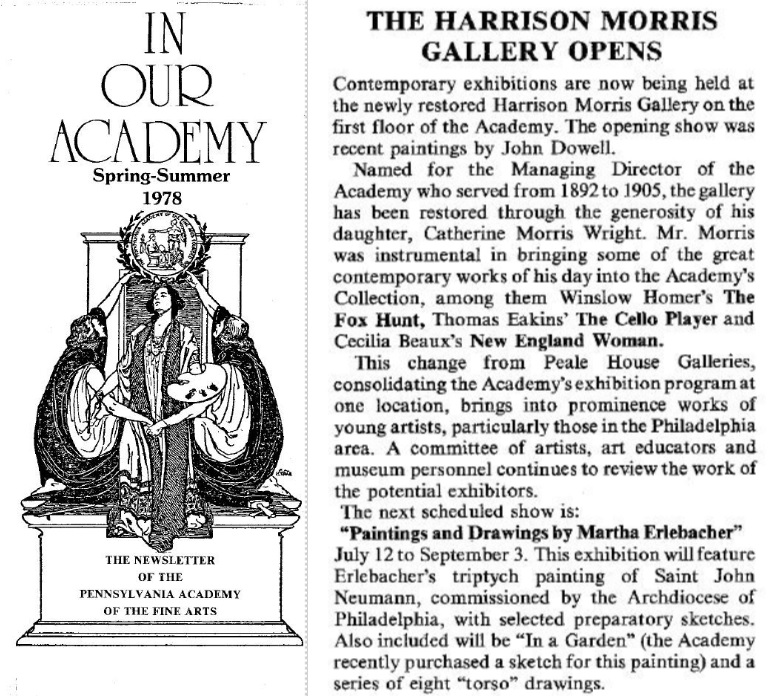

In Our Academy, PAFA Newsletter 1978 (RG.05.04)

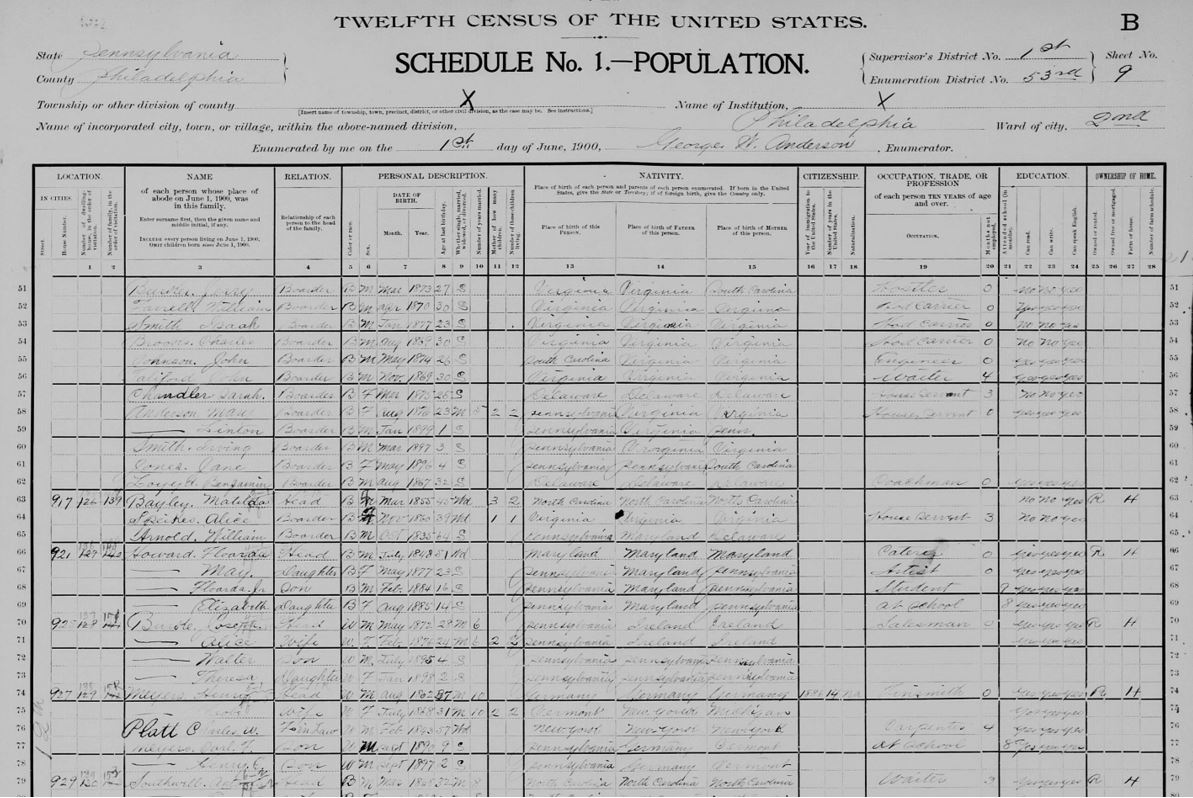

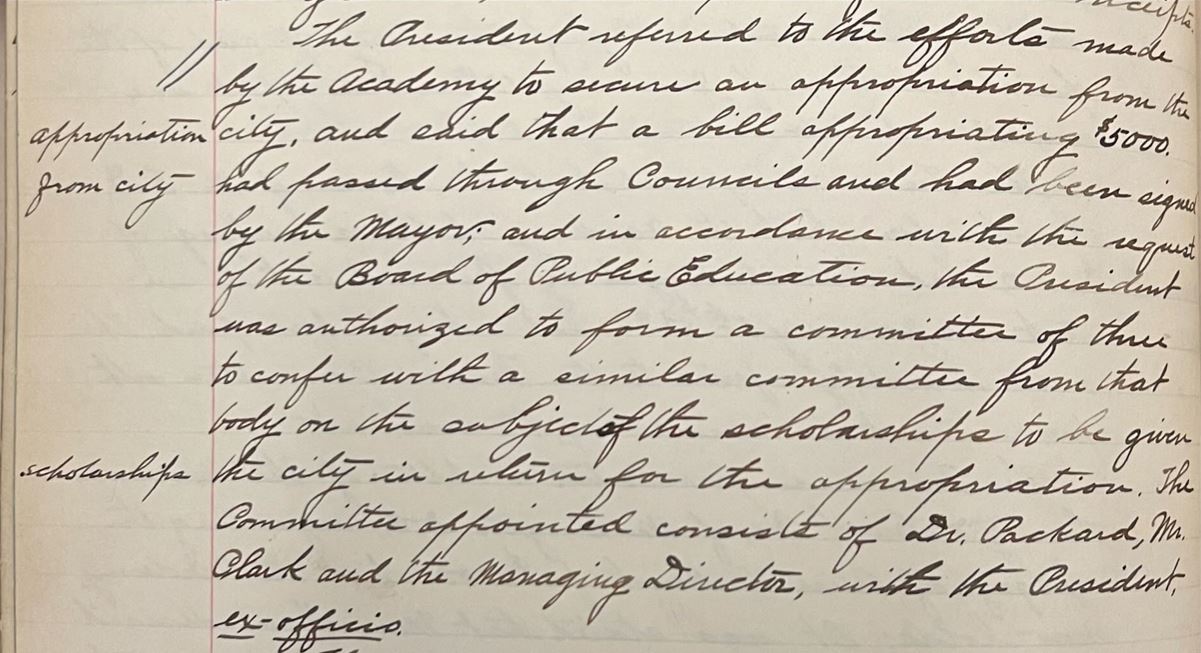

Named after Harrison S. Morris (1856-1948), the turn-of-the-century secretary and managing director of the Academy from 1892 to 1905, the Gallery was located on the ground floor of the Furness-Hewitt building; the space was restored by Catharine Morris Wright, in memory of her father.

To read more about Harrison S. Morris, please see: https://pafaarchives.org/s/digital/page/timeline

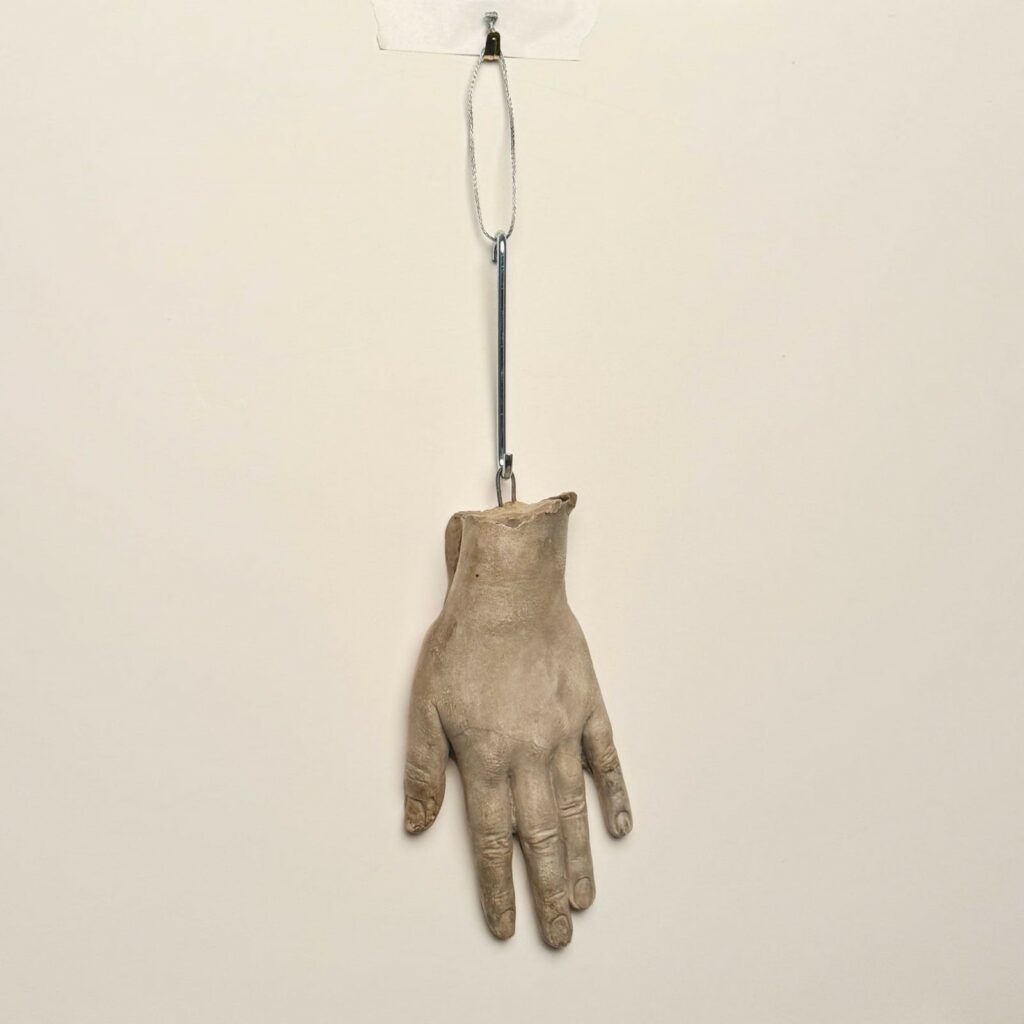

The Morris Gallery assumed the function of the Peale House galleries, which had originally featured works by both European and American artists. The broad focus of the Peale House galleries shifted in the early 1970s to highlight the work of younger, talented but unrecognized artists with special consideration given to those living or working in Philadelphia. The transfer of these exhibitions to the newly renovated and larger space of the Morris Gallery consolidated the Academy’s exhibition programs to one building and reaffirmed the institution’s continuing interest in contemporary art. From its inaugural exhibition in March 1978 (John Dowell: Recent Paintings), the Gallery has been a space for art of a range of mediums: drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, performance, and site-specific installations.

John Dowell: Recent Paintings (1978)

Steve Powers: The Magic Word (2007-08)

Woofy Bubbles performance (1984)

Lynn Denton: Sophia’s House— An Installation (1983)

After a series of part-time curators, the Academy hired a full-time head for the Morris Gallery program and for other contemporary exhibitions. Judith E. Stein held this position from 1983 until 1994. She was advised by the Morris Gallery Committee, consisting of board members, local artists, and Academy staff. In 1994, the gallery space was converted to a video and orientation theater. As a result, exhibitions were held in the main galleries for two years. The program resumed exhibitions in the original ground floor location in 1998. Subsequent Morris Gallery and Contemporary Art curators have widened the scope of this program, and the Morris Gallery Committee has been discontinued.

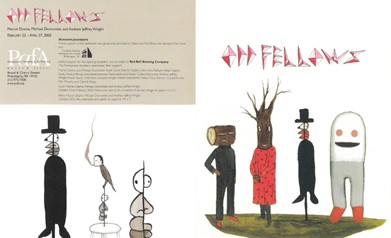

Odd Fellows: Marcel Dzama, Michael Dumontier, and Andrew Jeffrey Wright (2003),

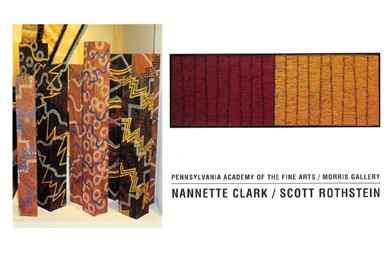

Nannette Clark and Scott Rothstein: Recent Work (1994)

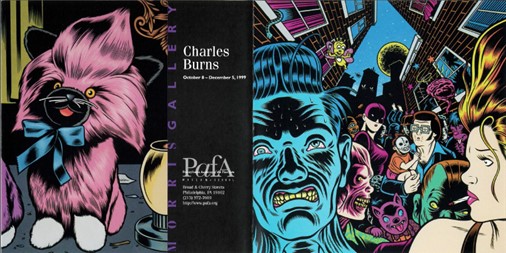

Charles Burns (1999)

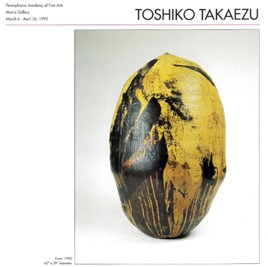

Toshiko Takaezu: Recent Work (1992)

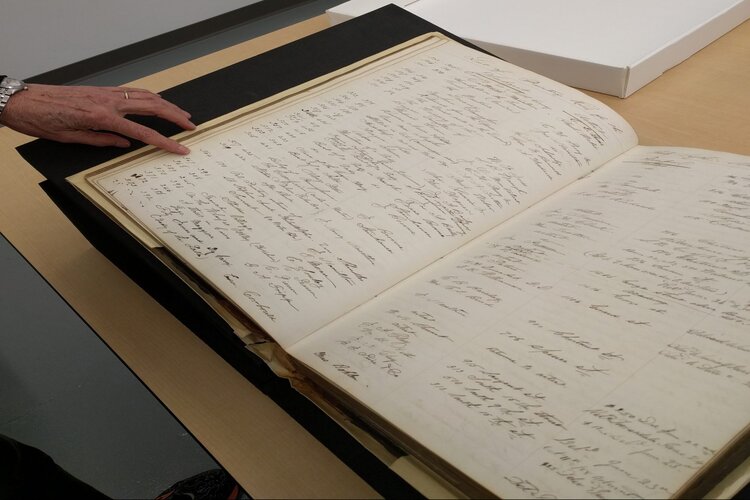

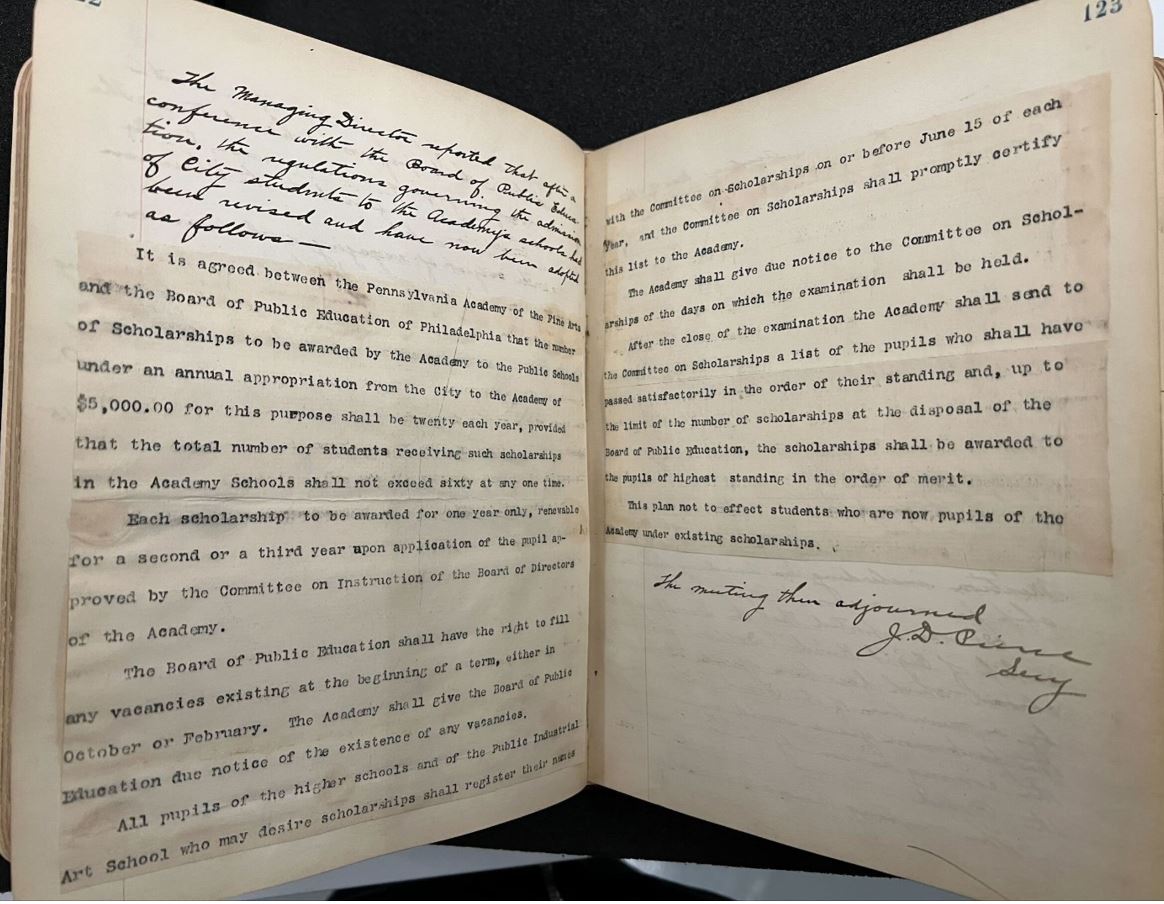

Various Morris Gallery exhibition programs (RG.02.06.05)

Throughout the years, over 1,000 photographs were taken of exhibitions held at the Morris Gallery between 1978 and 2009. All images have been digitized and organized by Museum staff and can now be viewed as part of the archive’s digital collection. Please also see the finding aid here: https://pafaarchives.org/PAFA-DigitalArchives/FindingAids/Photographs/PC.01.12_MorrisGallery.pdf