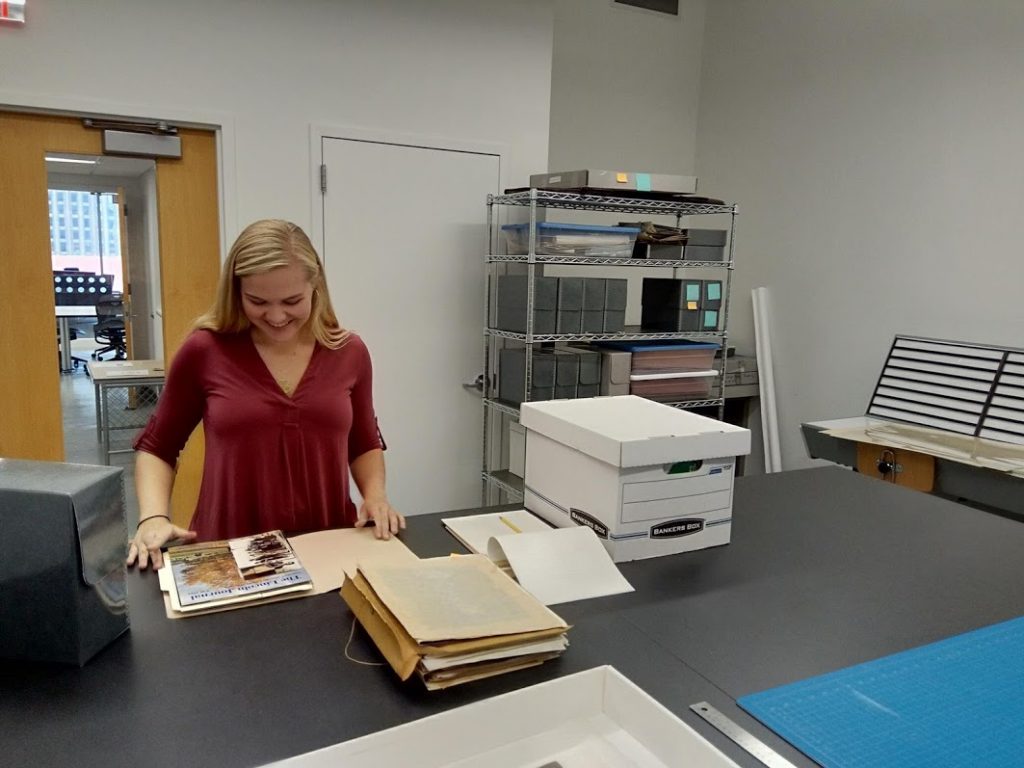

Contributed by Jahna Auerbach, Assistant Archivist for the John Rhoden papers

Lawrence Lew Kay found his way into our archives through his wife Richenda’s (wife of John Rhoden) papers. Lawrence was Richenda’s first husband, and through letters and newspaper clippings, we were able to understand his life.

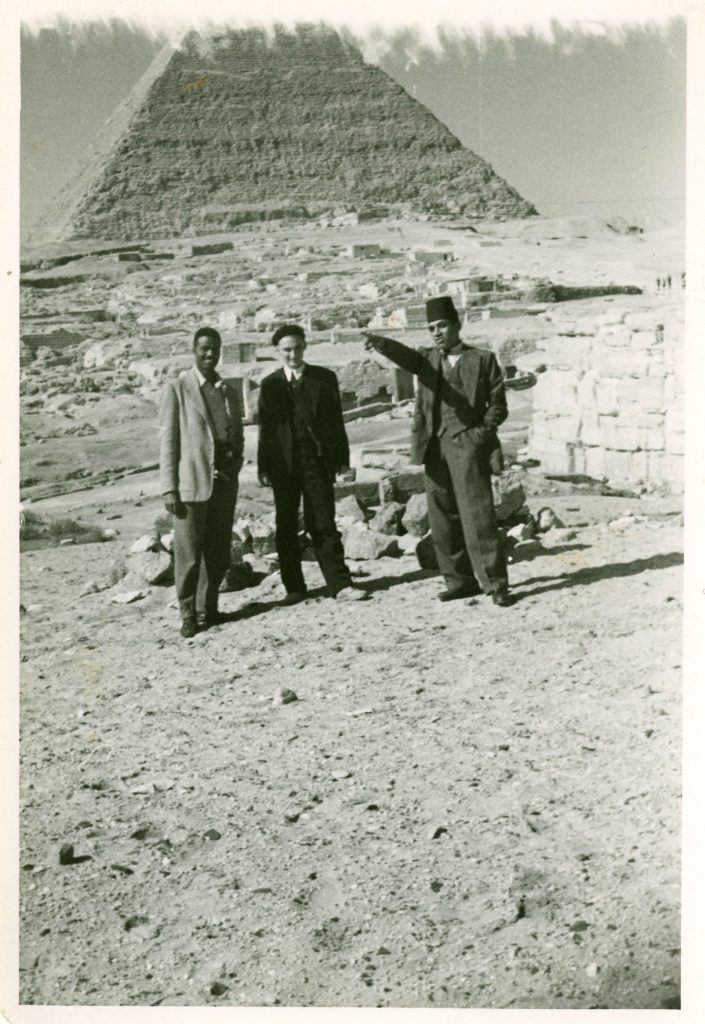

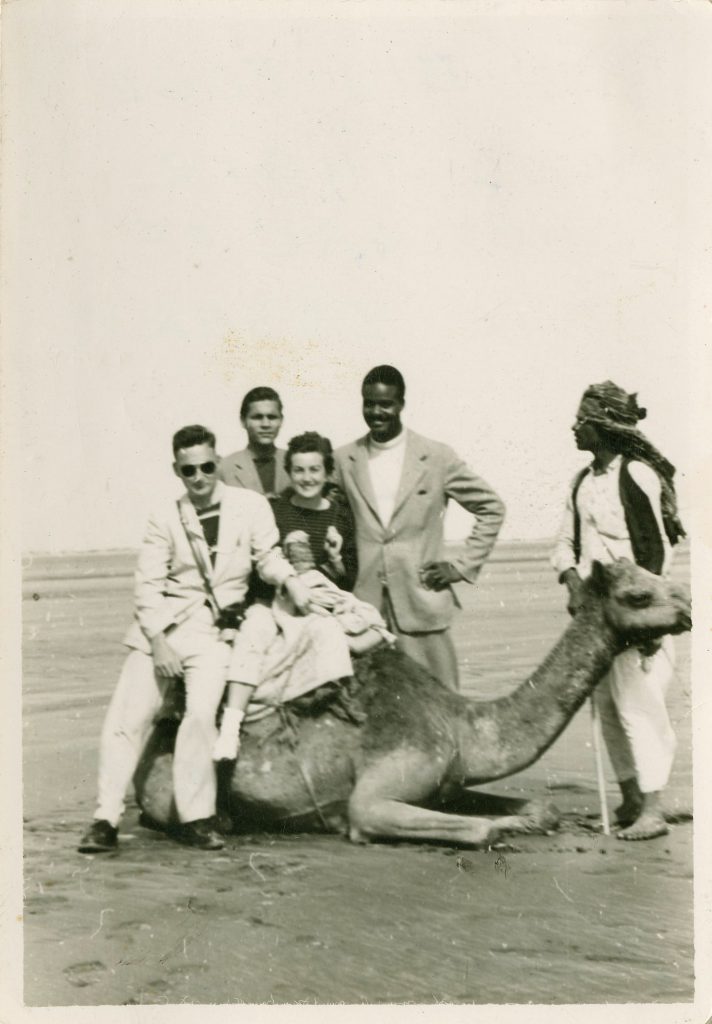

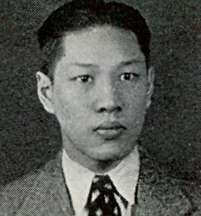

Lawrence was born in 1914 and lived in Seattle, Washington with his family. It is unclear through records if he was born in America or in Tangshan, China, where his family originated. Lawrence was a highly educated man; he received his B.A from Lingan University, China in 1937 and graduated from Harvard University in 1941 with a degree in Business Administration. Lawrence and Richenda Phillips met at the University of Washington in Seattle. They married each other soon afterward, just mere weeks before Lawrence was enlisted in the Air Force and sent to China as an American representative. Kay’s journey to China included a ship to Northern Africa, where he spent roughly a month. Unfortunately, Lawrence would never arrive in China.

While processing the papers, I was deeply enthralled by the many letters that Richenda received from Shan Yan Leung, nicknamed ‘Bird,’ who was a friend of Lawrence’s. Through these letters, we can understand Richenda and Lawrence a little better. It seems that Richenda and Lawrence married only a few days before he was deployed. It appears that Richenda did not know Lawrence’s family very well. It was Shan Yan Leung who gave her their address, and he asked Richenda to inform them of Lawrence’s status as missing in action.

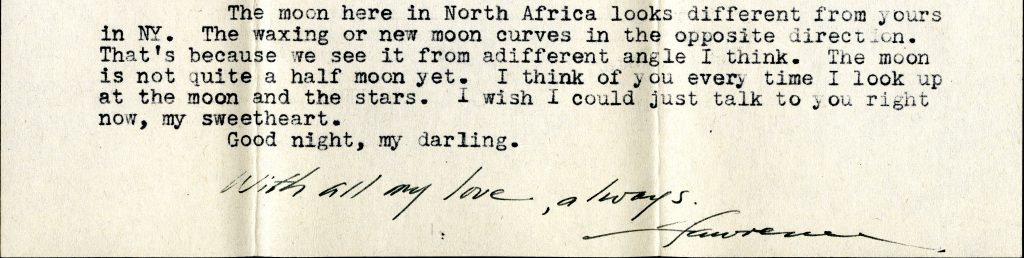

Lawrence writes to Richenda in detail in several letters while he is away. In these letters, he tells her about his travels to Northern Africa. What is most notable is the lack of food on the ship–Lawrence discusses in great detail how there was always a shortage of meals.

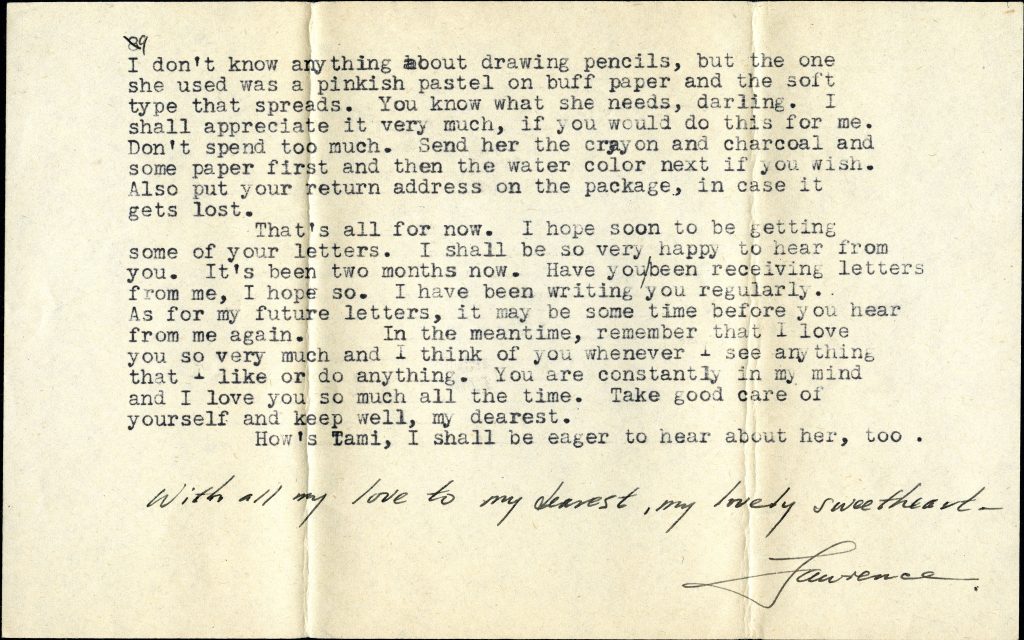

Even on land, Lawrence writes about hunting for food and locals offering him food. Lawrence tells Richenda about teaching fellow officers Mandarin and giving lectures about China. In his last letter to Richenda, Lawrence describes meeting locals and a young girl who is an artist. He asks Richenda to send him supplies for her. His last words to Richenda, “As for my future letters, it might be sometime before you hear from me again. In the meantime, remember that I love you so very much, and I think of you whenever I see anything I like or do anything. Take good care of yourself and keep well, my dearest. With all my love to my Dearest, My lovely sweetheart. – Lawrence” (MS_2019_01_1006i)

Lawrence died on November 27, 1943, at the age of 29 on the Rohna, a British troopship, which was attacked and sunk by a fleet of German planes in a coordinated surprise attack. The Rohna was scheduled to arrive in China where Lawrence would begin his service. Lawrence Kay was one of 1,015 America and British soldiers who died in this surprise attack. The attack on the Rohna marks the highest amount of America casualties in a naval attack in WWII, taking months for the American government to receive accurate information about the attack.

With the lack of constant contact, Richenda was left to wonder what happened to Lawrence. She began to hunt for answers, setting out to contact survivors of the Rohna. Through letters, Richenda learned that Lawrence escaped the initial barrage of missile fire with only minor injuries, but he was ultimately reported missing. For months she hoped he survived and was in an Allied hospital, unable to contact her due to his convalescence. As the months went on, it became clear that Lawrence had not survived the attack, and it is assumed that he tragically drowned after escaping the brunt of the German attack. Lawrence Lew Kay’s name was inscribed in a memorial for fallen Chinese American soldiers of World War II, located north of Hing Hay Park in Seattle, Washington.

Lawrence Lew Kay had a fascinating life, regardless of how short it was. It is clear from his accolades and accomplishments that he would have made a significant impact on both the domestic and international stage. While there are still many unanswered questions about his life and death, we hope to continue uncovering more about his life in the Rhoden papers.

This project, Rediscovering John W. Rhoden: Processing, Cataloging, Rehousing, and Digitizing the John W. Rhoden papers, is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation. Additional information about the National Endowment for the Humanities and its grant programs is available at: www.neh.gov.