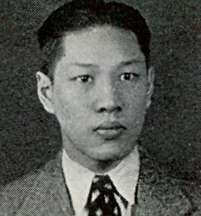

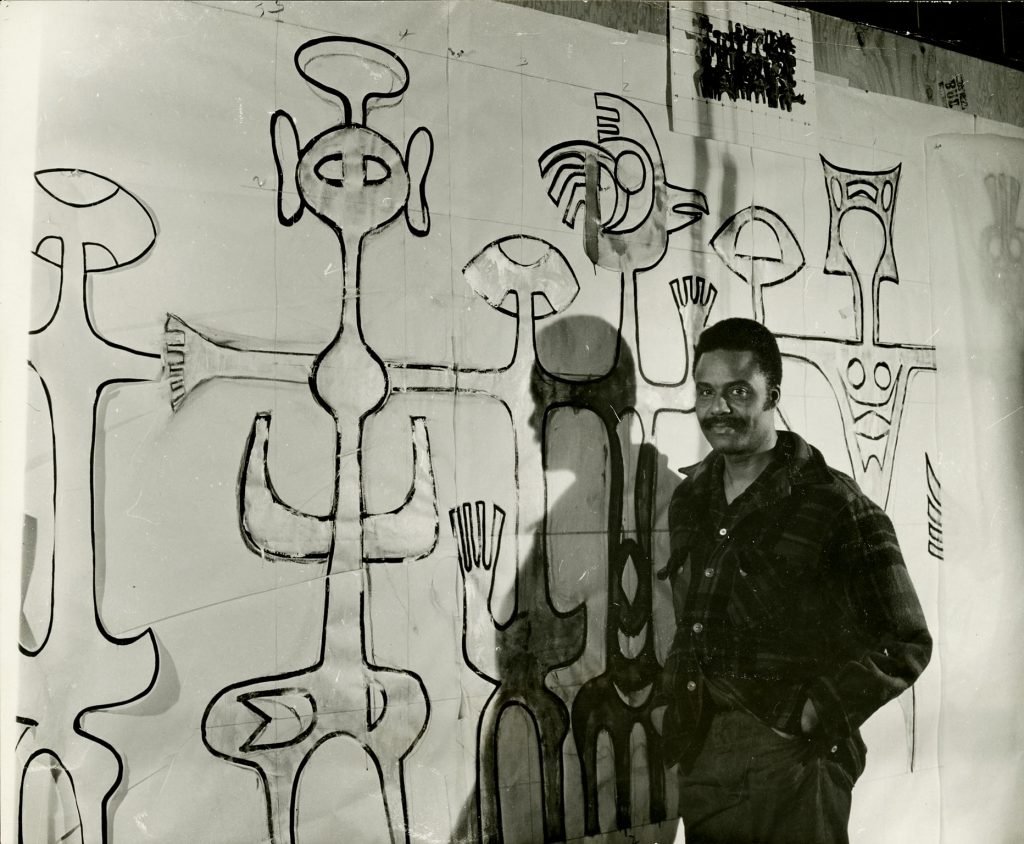

Contributed by Jahna Auerbach, Assistant Archivist for the John Rhoden papers

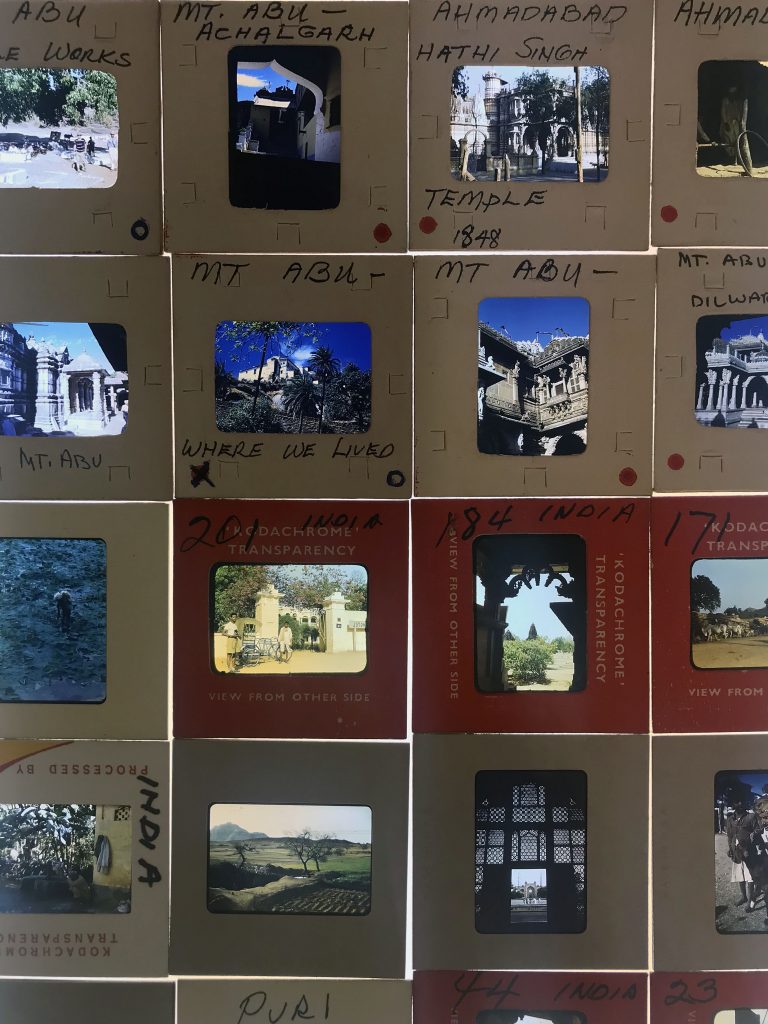

When the processing team began organizing the John Rhoden papers we were challenged with identifying over 2,300 slides from John Rhoden’s travels. A majority of the slides were unlabeled and unorganized. At best, some slides included labels inscribed on the physical slides with the name of the country or city name, usually misspelled. To create useful and meaningful descriptive catalog records, we have been researching the places John visited for the past few months.

Labeled slides being organized by country. Taken by the author on October 29, 2019.

Every detail is a clue

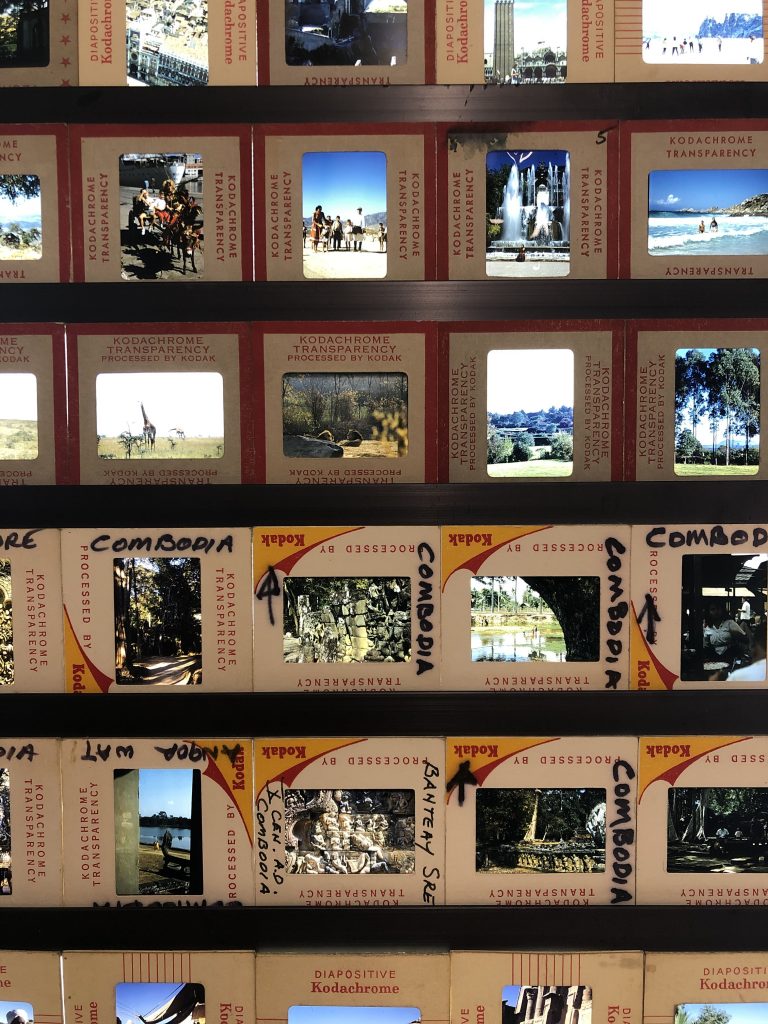

To physically arrange the slides, we first took a broad approach–identifying and organizing the slides by continent and then by country. This step required multiple passes between Kelin and I. The process included a significant amount of research, including looking up obscure architecture, street signs, traditional dress, flora and fauna, types of alcohol, types of transportation, and lots and lots of translation. Anything could be a clue. One day I spent hours looking at Soviet Era street lights in hopes of identifying a small town.

Other days were spent identifying countries by different languages that were found on street signs, store fronts, and license plates. In order to translate these clues, we not only used Google translate, but we sent images to family and friends who were from the countries that John had visited in hopes that they could help translate, identify languages, or identify alphabets.

Once we were able to identify the countries represented in a slide, we began identifying specific locations, typically historical sites and buildings. This meant spending lots of time in Google street view walking from, for example, one Russian cathedral to the next, trying to see if we could identify where John was from the smallest clues. Luckily, many of the sites John visited still exist!

Part Archivist // Part Detective

John Rhoden’s travel slides are color positive, 35mm film, and mounted between two pieces of cardstock. To identify certain places we had to utilize light boxes, magnifying glasses, digital scans and even Photoshop to create more sharpness and contrast between letters.

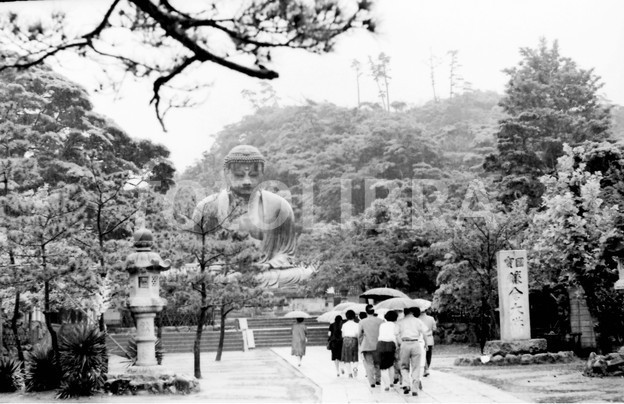

This image, taken between December 1958 and March 1959, is an example of a slide we needed to identify.

Here is an example of how we would identify a location on an unlabeled slide (above):

- The slide is unlabeled, but the characters on the stone sign/marker reveals it is more likely East Asia, based on Rhoden’s travel history.

- The characters resemble Japanese characters, so at this point we compared these images to other images we have that Rhoden labeled Japan.

- The subject of the image is a group of people (family) having their photograph taken in front of a stone relief sign. We deduced that it is likely a tourist area.

- After failing to find a tourist site in Japan with a matching sign we asked a family friend to translate the writing on the sign . We eventually learned that it says “National Treasure Great Buddha of Kamakura”

- Then we revisited Google maps to make sure we have the correct place. On google street view there is an identical sign, but it is in a different location and has a different base. (Image: below left, the stone marker in its current location.[1])

- Next we had to try to find images of the Great Buddha of Kamakura from the 1950s-1960s. Only through finding those images were we able to find confirmation of the stone sign, with the same base, near the Great Buddha of Kamakura. (Image: below right, In this photograph from 1968, the stone marker matches that of the slide.[2])

This is just an example of the identification process for one slide. But finding the identification for one slide can help identify many others. By identifying this one slide we now know that John traveled to Kamakura, Japan. There is a strong possibility that other slides from the area are also found in the collection, or at the very least, we can definitively label the slides “Japan”.

For other slides the subject may be somewhat generic. When a slide only shows, for example, a close-up of a roof or a cycle rickshaw, our Google searches tend to look like the following: “blue roof Russian cathedral Moscow” or “Indonesian cyclo”. We make educated guesses as to the location and continue to do so until we make an identification. Throughout the process, we gain new knowledge and awareness of specific regions, cultures, architecture, and geography. In fact, as we continue to learn more and more about certain countries, we become “subject specialists”: Kelin specializes in Europe; Hoang specializes in India and Italy; and I specialize in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Cataloging these slides have made me feel as if I have walked the streets of so many countries. I have also learned that many countries have developed so much over the last 70 years. For example, Seoul, South Korea in 1958 is unrecognizable compared to Seoul 2020, while other places have barely changed.

We would also like to use this blog post to thank everyone who has taken the time to help us translate and identify John travel photos. We wouldn’t have been able to do it without you!

R and L: Slides on a light table, in the process of being organized by country (November 12, 2019)

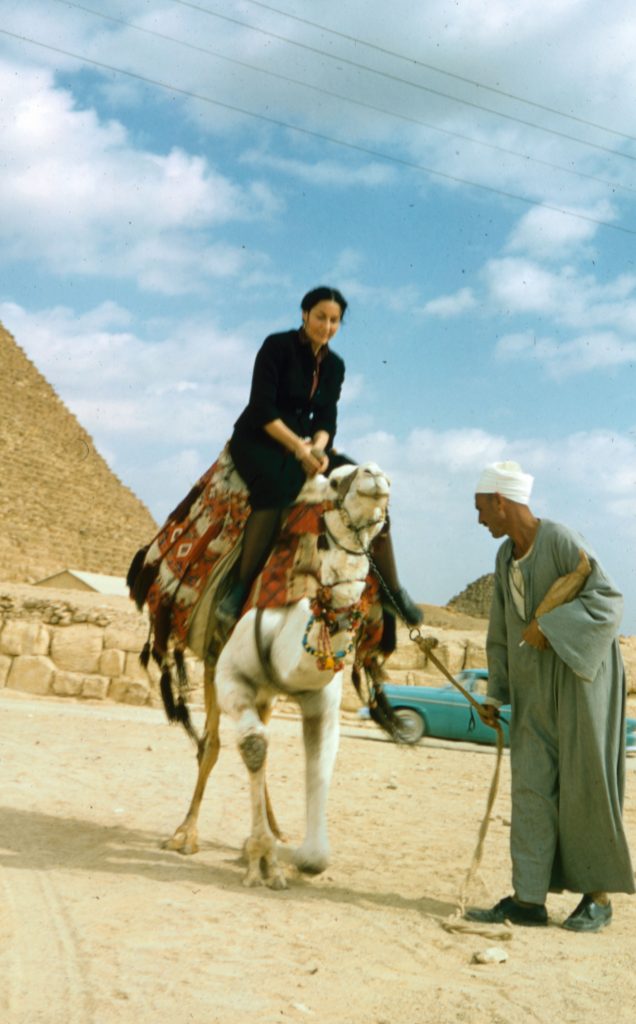

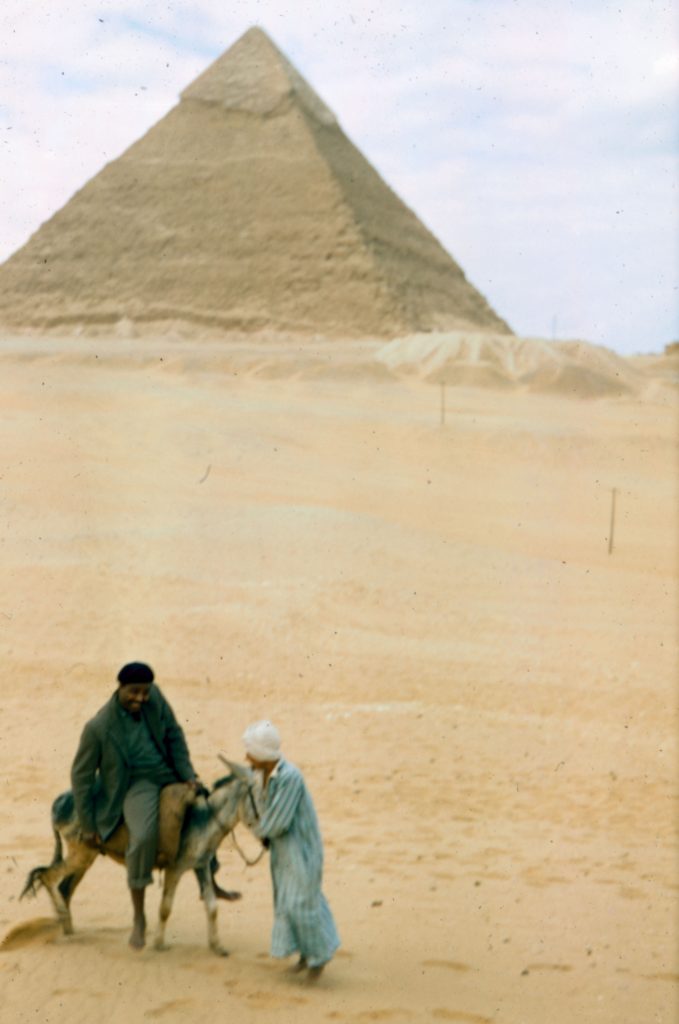

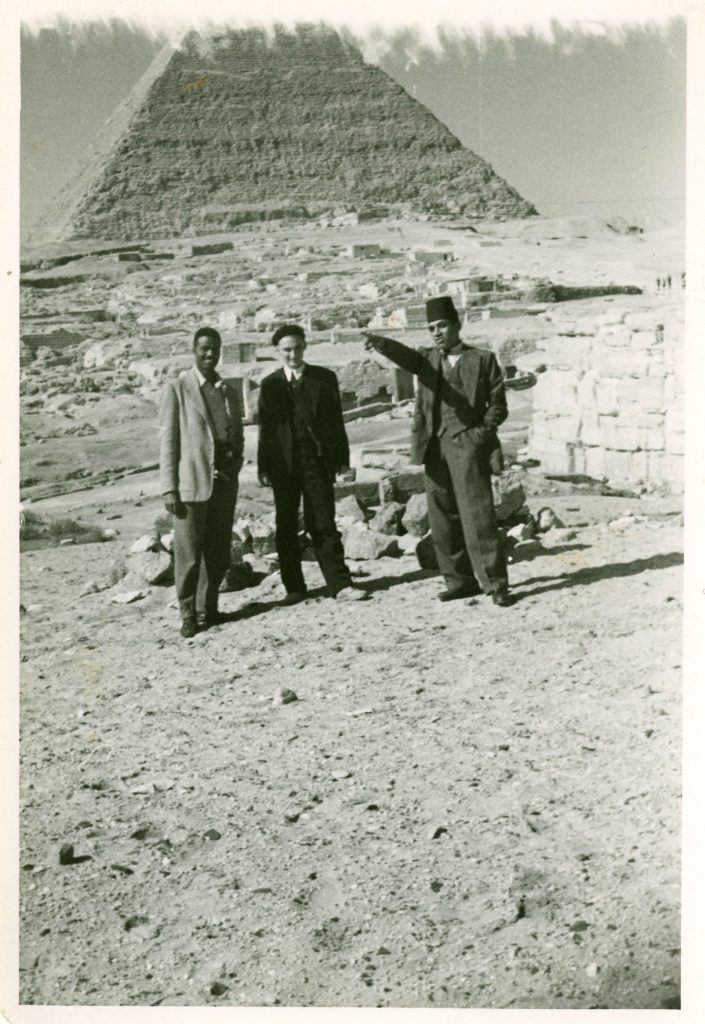

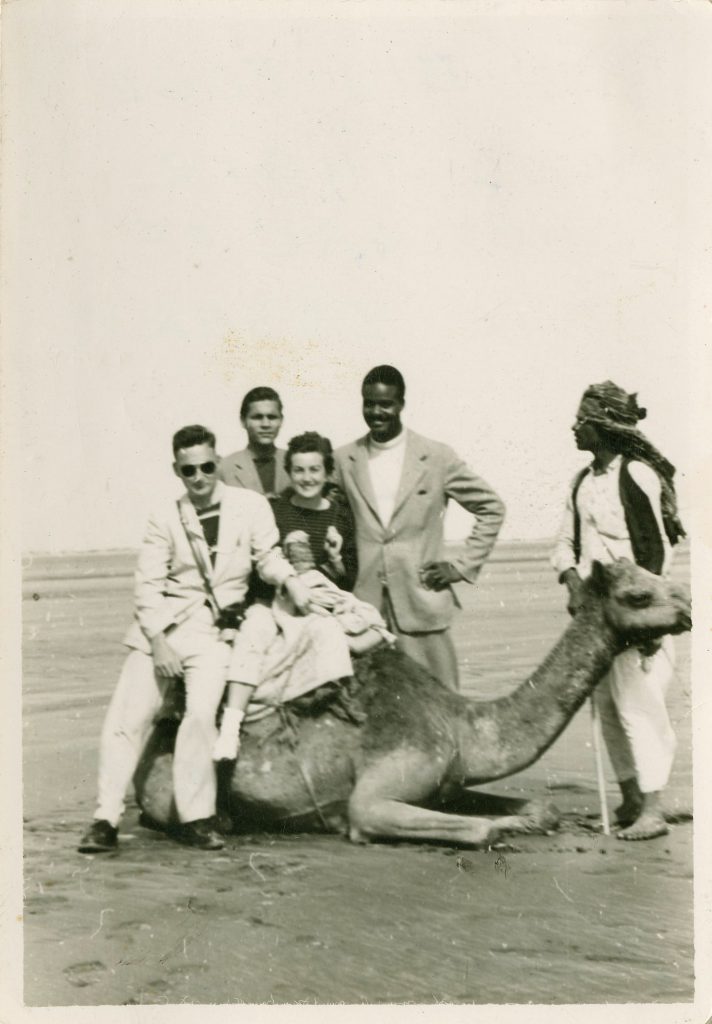

For reference, the following is a list of countries John traveled to between 1951 and 1963: (in alphabetical order) Armenia, Cambodia, Croatia, Egypt, England, Finland, France, Greece, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Japan, Jerusalem, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Monaco, Morocco, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Sardinia, Scotland, Serbia, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Syria, Thailand, Tibet, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and Zanzibar.

Image Credits:

- The Great Buddha of Kamakura from Google Maps. Captured by Google in 2010.

- Sparrow, L. (1968) “Great Buddha of Kamakura,” [digital image]. Retrieved from: https://www.fotolibra.com/gallery/977126/great-buddha-of-kamakura/?search_hash=744c19a5b3a19e0562dfc5cee5e8007a&search_offset=0&search_limit=100&search_sort_by=relevance_desc

This project, Rediscovering John W. Rhoden: Processing, Cataloging, Rehousing, and Digitizing the John W. Rhoden papers, is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation. Additional information about the National Endowment for the Humanities and its grant programs is available at: www.neh.gov.