Contributed by Kelin Baldridge, Project Archivist for the John Rhoden papers

During our three months away from the John Rhoden papers, we had one brief respite in the form of a Zoom lecture with our education department. During this lecture we spoke about John Rhoden, the John Rhoden papers, and the archive as storytelling. I noted one thing the archives tell us about John Rhoden that I would like to return to and elaborate on.

From the Rhoden papers, we learn that John was an ambitious businessman, far more so than one might expect from the stereotypical understanding of an artist. He was an active self-promoter and a highly successful networker.

The point to which I wished to return is that John was also resilient and persistent. He had a highly successful career and was recognized with some of the most notable accolades in the art world. However, he was no stranger to rejection.

John did not seem to be discouraged by rejection. In fact, he seemed to use it as fuel for his fire and an opportunity to improve and prove himself. The John Rhoden papers have several examples of John repeatedly applying to the same thing he was once rejected from, each time accumulating an ever more impressive band of advocates and curating a successful career that was impossible to ignore.

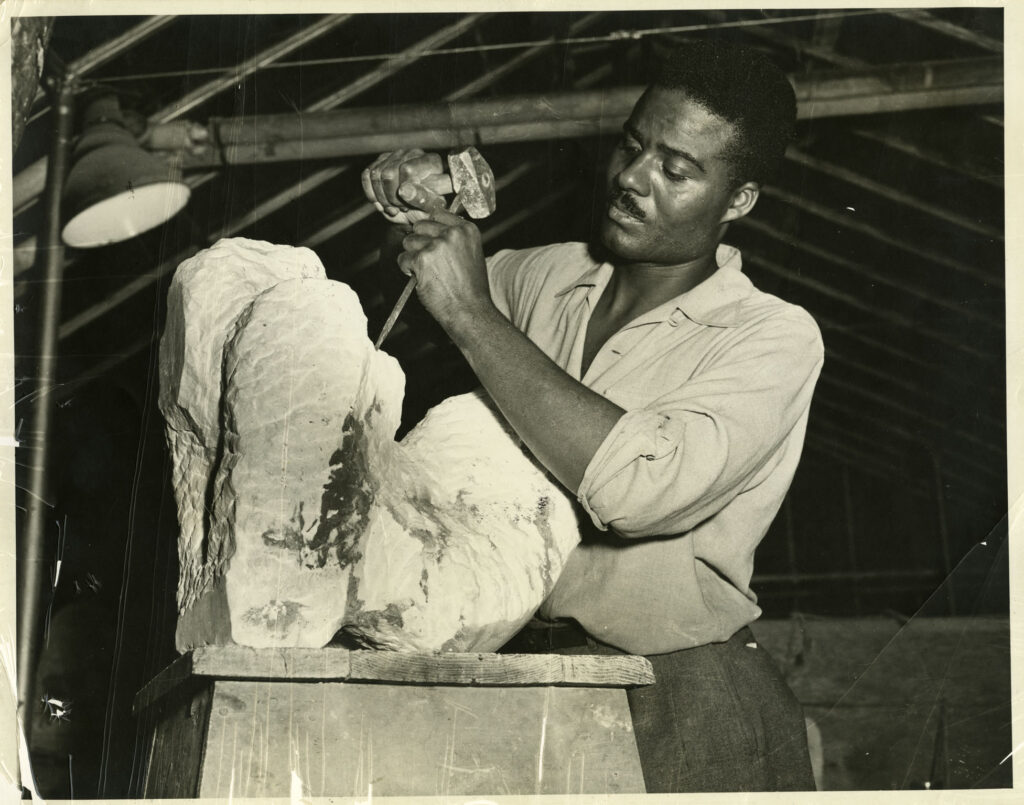

John Rhoden in 1946, the year he first applied for a Guggenheim fellowship.

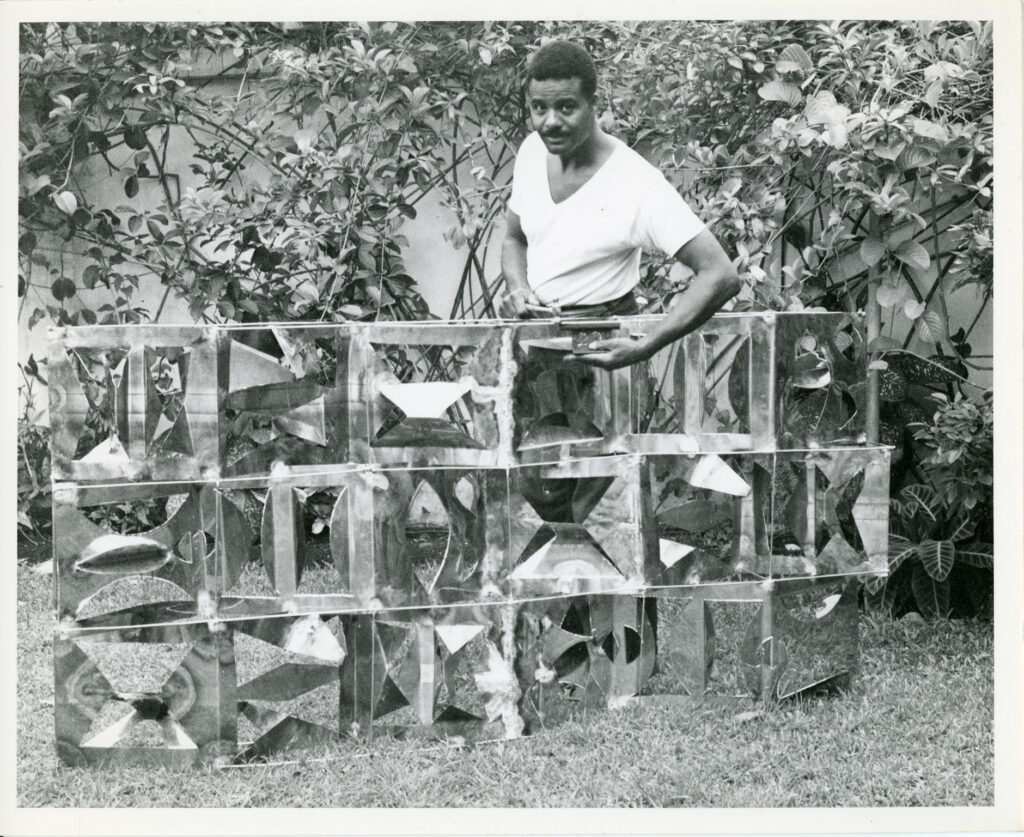

John Rhoden circa 1961, the year he finally received a Guggenheim fellowship.

The best-documented case of John’s resilience in the Rhoden Papers is his journey to earning the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship. In the Rhoden papers, we have evidence that John applied for the Guggenheim fellowship in 1945-1946, 1949-1950, 1954-1956, and in 1959-1961.

In 1945-1946, his first time applying to the fellowship, John was a young artist seeking educational support. He had yet to enroll at Columbia University, and his only experience to date was at Talladega College, The New York School of Art, and the New School for Social Research. A rejection letter in the Rhoden papers reveals that the Guggenheim fellowship was not meant for one “to study art as a pupil.” John simply hadn’t acquired the experience and knowledge to earn the fellowship.

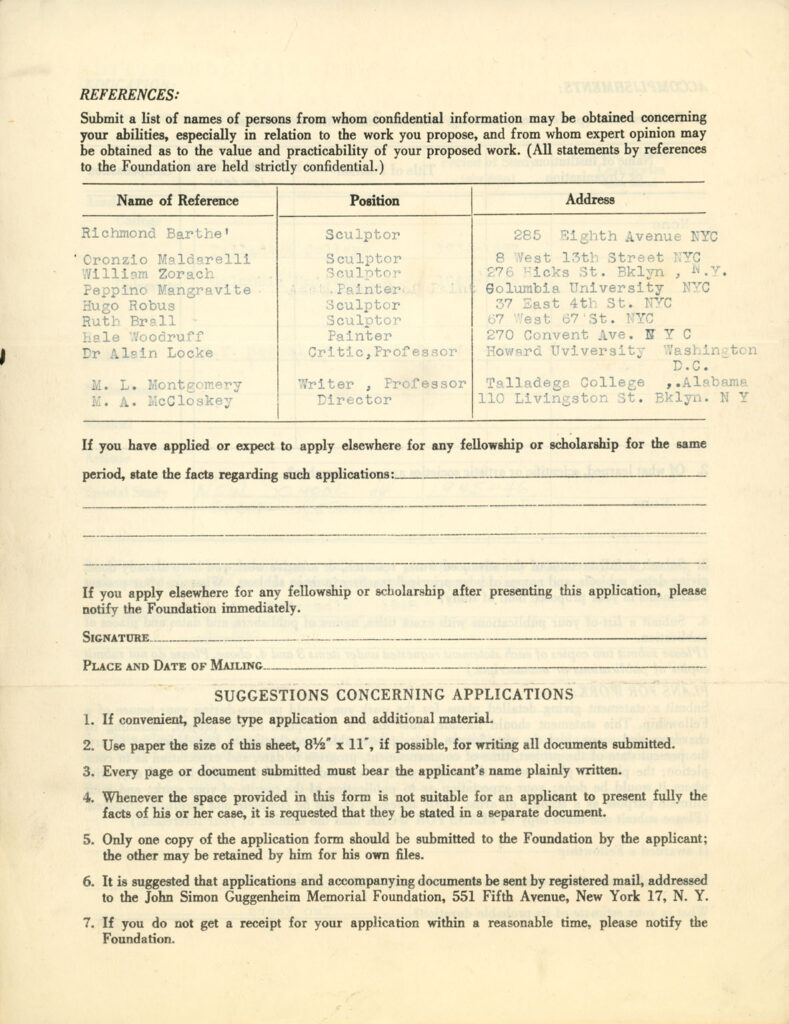

By the next time he applied in 1949-1950, John was nearing the end of his time at Columbia University and had been awarded a fellowship from the Rosenwald Fund in 1948. He had met many of the people who would serve as references on his behalf and had built a resume to include several first prizes in sculpture at Columbia. His artistic knowledge and experience had advanced and he was once again ready to apply to the Guggenheim fellowship.

He applied with an impressive round up of references, including Oronzio Maldarelli, William Zorach, Hugo Robus, and Peppino Mangravite, who all taught John at Columbia, Harlem Renaissance greats Richmond Barthé and Alain Locke, and early supporters from Talladega College, Hale Woodruff and Margaret Montgomery.

We do not have his rejection letter from 1949 to 1950, but it is clear that, while he was on the right path to being qualified, John was still somewhat green in his career.

John Rhoden’s reference list from his 1950 Guggenheim fellowship application

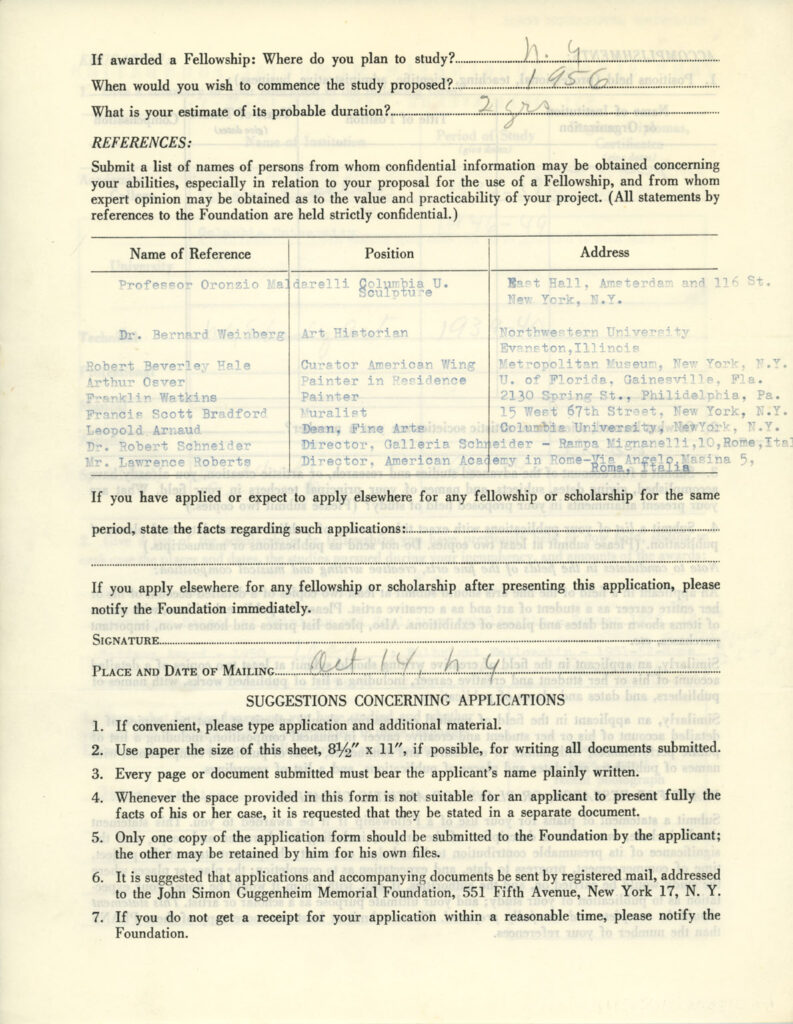

John Rhoden’s reference list from his 1956 Guggenheim fellowship application.

By John’s next application in 1954-1956, he had accumulated a Skowhegan School scholarship, a Tiffany Award, a Fulbright Fellowship, and the Prix de Rome. He had studied under many notable people and had begun to travel the world for his artistic endeavors. Oronzio Maldarelli once again served as a reference, and was joined by the likes of curator of paintings at the Met, Robert Beverly Hale, art historian Bernie Weinberg, artists Arthur Osver, Franklin Watkins, and Francis Scott Bradford, the dean of Fine Arts at Columbia, Leopold Arnaud, director of Galleria Schneider, Bob Schneider, and director of the American Academy in Rome Laurance Roberts.

Despite an impressive resume and a long list of highly regarded references, John, once again, was not awarded the Guggenheim fellowship. It is unclear if this was of his own volition, however, as his travels with the U.S. Department of State were extended through the latter half of the 1950s.

Finally, in 1959, John Rhoden writes to Dr. Henry Allen Moe of the Guggenheim Foundation, requesting that his application be reopened. At this point, John has received some of the most recognized fellowships and awards in the art world, studied at some of the most highly regarded institutions, and traveled the world serving as a representative of American art, accumulating international knowledge and spreading his passion and talent with every corner of the globe. Though we do not have his final application, it is no mental leap to assume that he had a round up of enthusiastic and recognizable references as well.

On May 22, 1961, John Rhoden was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship to cover two periods of time to “devote himself to creative sculpture.”

John’s journey with the Guggenheim Foundation fellowship is a beautiful story in perseverance and achieving success beyond one’s wildest dreams. Looking at the remaining evidence of this journey, I can’t help but think that each time John must have thought, “what else can I possibly do to be worthy of this?”

He went from a well-connected young artist with a respectable education to an Ivy League educated and decently recognized young professional to a highly educated, highly rewarded, internationally recognized, artist-representative of the United States. Each phase of his life expanded his world and each ceiling he broke opened new possibilities. When his achievements were not “enough” he kept pushing forward until his career surpassed anything the John that first applied in 1945-1946 could have imagined.

This story is one that shows both how relatable and how special John was. It is a beautiful lesson in how not to allow rejection defeat you, but rather inspire you to assess where you are, where you could be, and what you could do to get there.

This project, Rediscovering John W. Rhoden: Processing, Cataloging, Rehousing, and Digitizing the John W. Rhoden papers, is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation. Additional information about the National Endowment for the Humanities and its grant programs is available at: www.neh.gov.