Contributed by Jahna Auerbach, Assistant Archivist for the John Rhoden papers

Richenda Rhoden (1917-2016), born Richenda Phillips, was a Native American woman from the Cherokee and Menominee tribes. She was given the Menominee name Paytoemahtamo at birth, which means “Great Woman”. Throughout her life, Richenda would come to exemplify this apt title.

Richenda studied anthropology at the University of Washington in Seattle. While she was a student, she met her first husband, Laurence Kay, who she married in the early 1940s. Their correspondence during World War II clearly shows their deep bond and love for each other. However, Laurence did not come home from WWII; he was killed while on a ship in Northern Africa on November 27, 1943. In Richenda’s papers, there are many letters to her regarding to her husband’s whereabouts.

After the Laurence’s death, Richenda moved to New York City to start anew, where she became a hat model. During this time, Richenda enrolled in Columbia University to study Asian Art. At Columbia, Richenda met John Rhoden. They were married in Rome 1954, while John was studying at the American Academy.

In 1960 the Rhodens bought their house on 23 Cranberry Street, Brooklyn, New York. It was originally a livery stable, and the Rhodens poured all of their energy into renovating it. The house was complete with an elevator, and indoor and outdoor garden, and studio space. Inside their house was filled with their art. To get to know her neighbors, Richenda set up a little table selling crafts. This eventually turned into the Cranberry Street festival and prompted Richenda to found the Cranberry Street Association. Richenda loved Cranberry Street and saw the neighborhood as her extended family.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Richenda traveled all over the world with John. Because she was also a gifted artist, she was featured in many international news articles and was particularly well-covered by the German press. One article in particular wrote about her background and her artistic inspiration. The article talks about her connection to animals as a Native American. She is quoted saying that “I have always been a dreamer”.

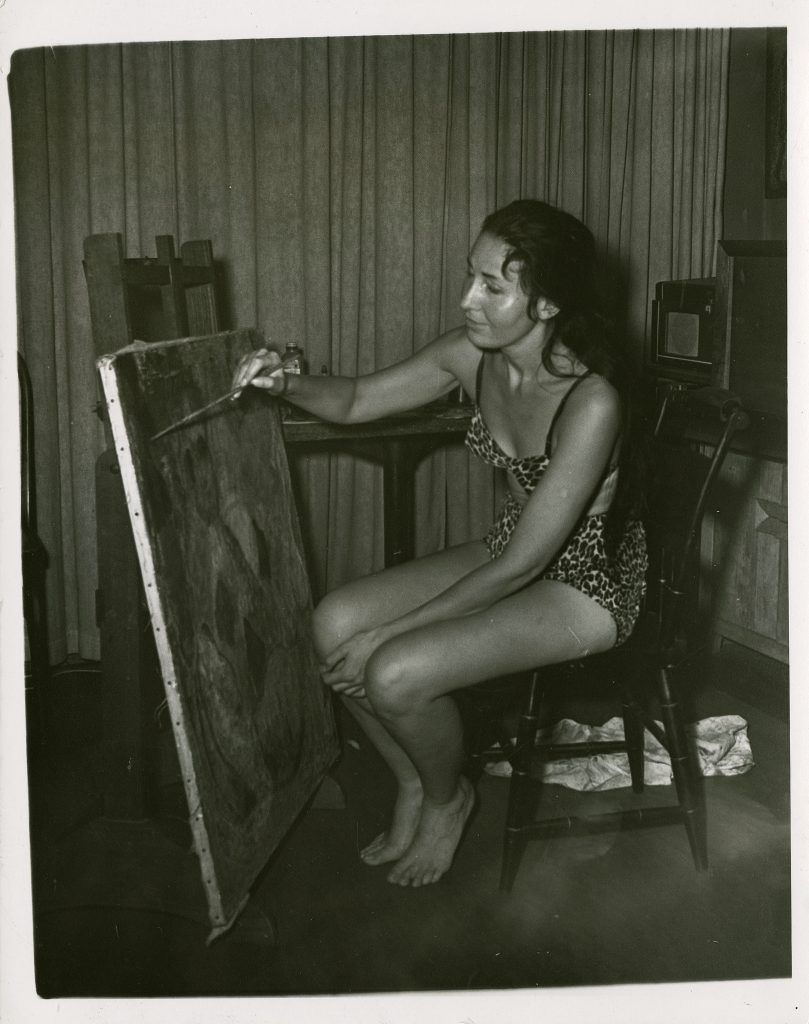

Richenda was an artist like John, but instead of sculpting she spent her days painting. She was inspired by folklore and mythology. Many of her works picture Native Americans as well as animals, nature and sacred geometry. While abroad with John, Richenda would take photographs of the people she met and collect their stories. She was also influenced by Marc Chagall, evidenced by one of her own paintings titled “Tribute to Chagall”. Over the years Richenda’s work fluctuated from being figure-based to being more abstract. That said, Richenda’s beautiful and powerful use of color remained present in her work throughout her life.

Richenda lived to be 99 years old. She painted almost everyday and due to limited mobility at the end of her life, she converted the freight elevator in her house into her studio. After she passed, Richenda had a retrospective at Soloway in Brooklyn New York, curated by Emily Weiner.

Richenda on vacation, undated.

Christmas with the Rhoden’s, 1984.

Richenda’s papers are only a small part of the John Rhoden Papers, but her presence is strong. From photos, it is easy to glean her personality. She loved her rooftop garden, traveling, and being surrounded by people and animals. Richenda was a radical woman of her time and an amazing artist in her own right. We hope through John’s papers we are also able to share Richenda’s story with the world.

This project, Rediscovering John W. Rhoden: Processing, Cataloging, Rehousing, and Digitizing the John W. Rhoden papers, is funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation. Additional information about the National Endowment for the Humanities and its grant programs is available at: www.neh.gov.